Reflections on Iran’s protests: Perils and potentiality

|

| Jina Mahsa Amini. Source: wikimedia commons |

What are the characteristics of the protests? Who and what drives them? And what are the vulnerabilities of the protest movement? The issue of vulnerability is central, as it may help external forces with little-to-no legitimacy within Iran to co-opt and/or manipulate the movement. This is particularly so when it comes to the Mojaheddin-e khalq group (the people’s mujaheddins), which enjoys no sympathy in Iran but has some credit within European and US policy-makers’ circles, and US-based Reza Pahlavi, the son of the last shah, who has proposed himself as the temporary leader of the movement, to lead a phase of transition from the old system of the Islamic Republic to a new regime, which however remains vague.

Mobilisation strategies and emancipatory potential

While presenting continuities, the current protest movement differs from previous mobilization cycles in its ability to hold together two elements that, until now, had been disjointed: radical direct actions, and the ability to attract support from a large section of the population, moving beyond class, ideological and sectarian/ethnic divisions.

It is not the first time that Iranians have mobilised en masse. The 2019 protests against the high cost of living managed to block roads, occupy squares and road intersections for months, putting into practice the lessons learned from other movements in the region (in Tunisia, Egypt, Syria, and Yemen). One of the greatest difficulties of the 2019 protest movement was however being unable to garner broad support. Composed largely of the poorer sections of society (who mobilised for the reintegration of subsidies for energy and food prices), the 2019 protests aroused fears in large parts of the middle and upper classes: fear of disorder and chaos, and fear that Iran may become like Syria, slipping into a spiral of growing instability.

This fear tells a lot about class divisions in Iranian society, and about the magnitude of the 2019 protests, which were large enough to set in motion a process of ‘syria-nization’. The current protests seem to be fundamentally different in terms of numbers, mobilisation strategies and support received. Perhaps precisely because of the smaller number of people involved, street tactics can be described as a ‘hit and run’ strategy, in which protesters take direct, even violent, actions against the police, and defend portions of the public space for limited periods of time, before moving elsewhere. Other forms of direct actions are less violent and include creating traffic jams on major roads in cities to slow down police and military convoys, and give the time to protesters to seek refuge and reach safe venues. Such direct actions, however, seem to be uncoordinated. The demonstrators do not seem to move as, for example, they used to do during the 2009-2010 mobilisations - the so-called Green Movement - against the re-election of Ahmadinejad to the presidency of the Republic. Then, calls for mobilisation originated from the leaders of the Movement (Mir Hossein Moussavi, Mehdi Karroubi and their circles) and included details about the place (or places) and time of meetings and were circulated online and offline. Some might remember the crucial role played by Moussavi and Karroubi's electoral committees, websites such as www.balatarin.com as well as the important role that text messages had. Meetings tended to be bigger than at present. According to a contact in Iran, the 2022 direct actions are carried out by rather small and cohesive groups of people acting autonomously, without coordination.

At the same time, we also have a more traditional type of mobilisations led by local and national organisations which have existed for years and which engage in ‘classical’ forms of protests such as strikes and demonstrations. For example, during the weekend, university students’ organisations have been on strike to protest state violence and the closure of university campuses throughout the country. They have also called for large, nation-wide protests during the weekend, a call which successfully brought people to the streets. Other organisations, which have been mobilising over the past year for specific reasons, are extending support for the protesters. This is the case of the semi-legal teachers’ union , which called for a strike and has led a wave of nationwide strikes during the summer of 2022 demanding a pay rise for teachers, and also the case of the union that formed around the Haft Tappeh sugar cane factory, which has been occupied and self-managed for some time. The fact that the current protests are able to support by more established organisations tells us that political conflicts in Iran have been present for some time.

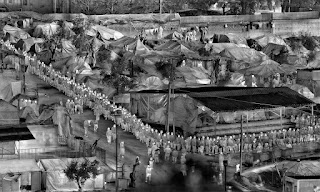

|

| Iran Protests, Tehran, Sept. 2022. Source: wikimedia commons |

Another element that distinguishes the current protests from those of the past is the generational composition. From the videos that have been circulating on social media, and from the testimonies of people in Iran, it can be deduced that young people and teenagers are leading the protests. These are above all the young women who we have been seen burning their veils and cutting their hair; we have seen them confronting those who scolded them and engaging in direct actions against the police. Young men too stand in the streets with them. Despite the leading role of young people, it is essential to note that the protests are intergenerational, with people of different ages engaging in direct actions, applauding the girls who take off their veils and defending women attacked by police agents. Intergenerational participation is made possible by the fact that pensioners in Iran have been mobilising for several months to protest against a financial scam they were victims of – a scam operated by the Iranian social services body managing their pensions. Additionally, during the summer of 2022 the pensioners’ protests have intersected with those of traders against galloping inflation, thus offering a fertile ground for cooperation.

Finally, it is crucial to recognise that these protests, regardless of how they end, are of unprecedented strength because they centre the issue of women’s bodily autonomy. The power of the state (or other authorities) to cover and uncover the body of women – be it the compulsory hejab in Iran, or the hejab ban in European liberal democracies – is one of the foundations of patriarchy. What we have today in Iran is a movement that wants to dismantle this very patriarchal foundation. It is a movement with enormous emancipatory potential because it is intersectional and speaks to women in every corner of the planet. Women living in Italy, ruled by the far right, women living in Texas, Alabama, or Arkansas, and women living in Modi’s India or Bolsonaro’s Brazil, know very well that today’s authoritarian politics makes the attacks on women’s reproductive rights and bodily autonomy one of its foundations.

The difficulty that some observers have in seeing this extraordinary emancipatory potential arises from a difficulty to recognise and acknowledge the power of feminist struggles in general. Additionally, when such a potential comes from Iranian, that is, non-European or North American, women, it is even more difficult to see and acknowledge its power.

.jpg) |

| Iran protests, Tehran, Sept. 2022. Source: wikimedia commons |

Weak leadership and the risk of co-optation

These days, many people are wondering who and what is leading the protests. In fact, there is no leadership that coordinates and gives a political-strategic direction to the protests with legitimacy from below. Although the protesters’ demands are clear – the dismantling of the moral police (gasht-e ershad) and the abolition of the compulsory veil – there is no collective entity capable of coordinating the other issues that intersect with these demands: how to handle the nuclear negotiations, how to dismantle political authoritarianism and support change, and what political change ought to look like.

The genealogy of these protests is long and rich. We have the feminist struggles of the past, which had a great deal of visibility in the 1990s and 2000s, and which demanded legislative reforms and led social and even linguistic change during those years; and we have the political prisoners, who include in their midst feminist leaders with great national and international visibility, such as Nasrin Sotoudeh and Narges Mohammadi. The absence of a collective entity that can legitimately claim the leadership of the protests, however, makes the movement vulnerable to the attempts to manipulate and co-opt it that we have seen recently. This is the case of Reza Pahlavi and the people’s mojaheddin, but also of the imperial feminism of Massoumeh Alinejad, who has flirted with neo-conservative and Trumpian elites and who self-proclaimed herself as leader of the movement, all the while silencing the Iranians’ anger at and critique against Washington’s ‘maximum pressure’ policy and international sanctions. Although these might seem as clumsy moves today, they are real attempts to impose a hegemony where no other voice is present or coherently articulated – attempts that also enjoy political and economic resources. Similarly, the support by far-right female leaders, such as Italy’s Giorgia Meloni, for Iranian women is incoherent, performative and dangerous. In Iran, it is often said that you cannot support Iranian women’s struggle for self-determination while denying the same to the women in your own country – be it free and legal access to abortion, or the choice to wear the veil.

It is extremely difficult to assess the trajectory of the ongoing protests. However, these protests have enormous significance in the Iranian context. This is a movement that, for the first time since the beginning of the Eighties when the veil was made mandatory, is not only repoliticizing the question of state control over women’s bodies, but is also bringing it to the streets, triggering riots and protests all over the country. It is also an expansive movement in terms of the issues that it intersects with, from structural racism to police brutality and economic injustice. These protests might mark a point of no return in state-society relations: increasingly authoritarian, the state does not grant any space for dissent and has been repressing all movements for change, which have been left with no other option but becoming more and more radical, indicating a growing distrust in institutions.

*This piece is based on an article by the same author and published in Italian in Jacobin magazine, available at https://jacobinitalia.it/un-movimento-nuovo-con-radici-antiche/.

Comments

Post a Comment