Investigating the mental health and wellbeing of young Arabic-speaking adolescents who have migrated to Ireland from conflict-affected countries

Families from refugee backgrounds living in high income countries, often experience poorer psychological and wellbeing outcomes due to the many health, social and cultural challenges experienced post-migration (Fazel et al. 2012). Over half of the world’s refugees are children aged under 18, many of whom have come from conflict-affected countries where they have experienced multiple traumas. The long-term effects of pre-migration traumas, including conflict, violence, separation and/or loss of family members, may persist without adequate supports, potentially exacerbating existing difficulties. Post-migration, refugees commonly face stigmatisation and discrimination in their host countries, contributing further to poor mental wellbeing.

In response to the refugee crisis in 2015, the Irish Government established the Irish Refugee Protection Programme (IRPP), with a commitment to accept up to 4000 refugees through the European Union Relocation Programme and the UNHCR-led Refugee Resettlement Programme. The majority of programme refugees arrive from Lebanon and Jordan with others seeking asylum through the International Protection Office. Currently, over 3200 have resettled in Ireland, comprising mainly Syrian families, 40% of whom are minors. In 2019, the Government agreed to a further intake of 2900 refugees up to 2023, through a combination of resettlement and community sponsorship initiatives. To date, little is known about how these children and young people are faring in their host countries. How are they being supported in schools and in the wider community? What about their mental health and wellbeing – and to what extent have they been affected by the current pandemic?

The SALaM Ireland research

The SALaM (Study of Adolescent Lives after Migration) Ireland study is led by Professor Sinéad McGilloway, Founder/Director of the Centre for Mental Health and Community Research (CMHCR) at Maynooth University (MU) Department of Psychology and Social Sciences Institute, and conducted in collaboration with senior co-investigators, Dr Rita Sakr (MU Department of English) and Dr Anthony Malone (MU Department of Education). Yvonne Leckey (CMHCR) is the Project Manager.

The study is part of a larger international research programme called ‘SALaMA’ (Study of Adolescent Lives after Migration to America) led by Washington University, St Louis (USA) in partnership with Qatar Foundation International (QFI), who fund the research. The aims of this research are to: (1) assess the mental health and psychosocial wellbeing of students aged 13-18 years who have resettled to Ireland from Arab-majority countries; and (2) identify and explore the sources of daily stress in these students’ lives, as well as the supports available to them.

The SALaM Ireland study is the first research of its kind in Ireland, and coupled with the data from the US, will generate the most extensive data set worldwide on the wellbeing of Arabic-speaking newcomer students re-settled to high income countries. The study findings will provide important insights into the experiences and needs of these young people and the nature and extent of any stress that they may be experiencing in their daily lives, both in school and the wider community. It will also highlight ways in which schools and communities support these students as they adapt to life outside their country of origin.

Early findings

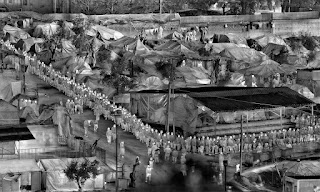

The first phase of the SALaM Ireland study involved interviews with over 50 key stakeholders, who provide a wide range of community/voluntary and statutory sector services and supports to Arabic-speaking (and other) families across Ireland. We outline here some of our preliminary findings which focus primarily on ‘programme refugees’ (as part of the IRPP) who resided in emergency centres prior to resettlement in the community.

Interviewees identified numerous challenges faced by adolescents in adjusting to an unfamiliar culture and context. Our findings, in line with international evidence (Green et al. 2017), demonstrate how Arabic-speaking young people face considerable barriers to integration due to a lack of formal schooling and poor English. While some refugees were relatively proficient in English, most had little, or no, English to sufficiently engage in learning. Despite this, teenagers “were placed in classes that were age-appropriate with no English, with no understanding of the curriculum.” Low levels of education and/or disrupted education were also found to significantly affect students’ capacity to learn. For many refugees, prior access to education was often limited and some were non-literate in their own language or had never attended school. Interviewees described a number of language and literacy barriers: “a lot have literacy problems, no Arabic and no English. A lot of them didn't even go to Arabic school.” Students have had to quickly adapt to the teaching, curriculum and structure of a formal classroom environment which, for many, was often overwhelming.

One participant described the loneliness and isolation felt by teenagers in the classroom: “So imagine a child who never went to school. They're being asked to be in formal education. They don't have the language so they're just lost.” English proficiency was also vital for forming friendships and establishing connections within the wider community: “the education system didn't seem to be supporting them in terms of English language, which let's be honest, is the fundamental of integration, … [and] being able to express yourself in the country.”

Refugee children are at increased risk for developing mental health problems, not only due to pre-migration adversity but also the need to adapt to the host society more quickly than their parents (Henley and Robinson, 2011). In our study, mental health professionals reported increased levels of anxiety, distress and isolation amongst these young people. Teenagers were “more likely to remember the war … maybe have been injured; they are more likely to remember people that they have lost” and the subsequent trauma often resulted in, amongst other things, hypervigilance and concentration difficulties. One interviewee poignantly described the burden of loss carried by teenagers and relayed their reluctance, in particular, to form friendships when living at the emergency centre, knowing that they will be eventually resettled elsewhere:

“I had friends in Syria, and I had to say goodbye to them. Then I made friends in Lebanon and I had to say goodbye to them. My parents want me to make friends here. But why should I do that? Because we'll be moving from here. So I have to say goodbye again.”

Younger children were seen as quick to anger, “wilful and practically feral”, most likely as a result of having previously lived in challenging camp conditions where “violence was normalised ... hitting and punching and scratching”. Participants reported that adults, predominately men, typically present with more complex levels of psychological distress due to “compounding levels of trauma, and compounding levels of loss and separations”. This kind of parental trauma coupled with post-migration stressors are a source of concern in view of the evidence to suggest that these also increase the risk of psychological problems amongst children (Bryant et al. 2018).

So how well are schools in Ireland addressing the needs of their migrant students, and in particular, those Arabic-speaking students that are the focus of this study? Due to COVID-19 restrictions, we have been able to conduct only a small number of interviews with teachers/educators, to date, but the findings so far suggest that, in general, schools have limited experience of teaching refugees and lack adequate resources to appropriately address the language and socioemotional needs of their students. Despite this, some schools are delivering a range of supports and programmes to promote integration and facilitate school belonging, including buddy or wellness programmes, as well as implementing restorative and trauma-informed practices. Educators referred, in particular, to the importance of promoting a positive school ethos and environment to create a sense of belonging for all, and addressing diversity issues among students. For example, one interviewee commented:

“I think that the kindness of schools goes a long way. I know that people aren't educated about maybe the Muslim faith or dress codes … how our food and all of those things are important. But I think [what is] more important is the ethos of the school.”

We hope to collect more data from school personnel and also from refugee families in the next phase of our research.

Unsurprisingly perhaps, another key finding from our study was the distinctive challenges faced by programme refugees due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Refugee families, who had not yet been resettled, were restricted to reception centres with limited access to services and little/no opportunities for socialisation. Students were hugely affected by school closures, in particular, and in spite of the online provision of language support and schooling, they continued to struggle with digital learning and reliable internet access.

Overall, our findings indicate that language barriers had the most significant (negative) consequences for academic learning and integration within the wider community. The next phase of our research involves collecting data from adolescents in schools in order to assess their psychosocial wellbeing and explore inhibiting or facilitating factors in this regard. Due to ongoing COVID-19 restrictions, this phase has been considerably delayed, but data collection is due to commence in 2022. Caregiver perspectives will also be gathered during this phase to better understand the experiences, and challenges for families, of resettling in Ireland. Collectively, the findings should help to inform school practices and policies to better support this population in Ireland, the US and possibly elsewhere in the world.

The SALaM Ireland Study will conclude in 2022. For further information on the study, please see our website: (www.cmhcr.eu/salam) or contact Yvonne Leckey (Yvonne,Leckey@mu.ie) or Professor Sinéad McGilloway (Sinead.McGiulloway@mu.ie) (@CMCHR_maynooth; @IrelandSalam).

References

Bryant, R. A., Edwards, B., Creamer, M., O'Donnell, M., Forbes, D., Felmingham, K. L., ... & Hadzi-Pavlovic, D. (2018). “The effect of post-traumatic stress disorder on refugees' parenting and their children's mental health: a cohort study.” The Lancet Public Health, 3(5), e249-e258.

Fazel, M., Reed, R. V., Panter-Brick, C., & Stein, A. (2012). “Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in high-income countries: risk and protective factors.” The Lancet, 379(9812), 266-282.

Green M. (2017). “Language Barriers and Health of Syrian Refugees in Germany”. American journal of public health, 107(4), 486. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303676

Henley, J., & Robinson, J. (2011). “Mental health issues among refugee children and adolescents.” Clinical Psychologist, 15(2), 51-62.

Comments

Post a Comment