Power and conflict versus the global development: a study of Iran-US relations

By Dr Amin Sharifi Isaloo

This paper presents sociological and anthropological theories to examine the linkages between conflict and development, particularly the world power structures and interests which contribute to the continuation of violence within and between countries. Concentrating on the international relations, the purpose of this paper is to advance an understanding of global development in phases of conflicts and to discuss how conflicts affect development. In other words, a particular focus on the international tension is taken to illustrate destabilisation of global development by powerful states which leads the world into an uncertain future.

In reaction to the welcome speech of US representative Adlai Stevenson, who reiterated the US commitment to helping African countries in the General Assembly, Jaja Anucha Wachuku who was first Nigerian ambassador and permanent representative to the United Nations in 1960, responded: Well, the West will have to pay for its decades of colonialism, and we are not here with our hand out asking for your charity, Ambassador Stevenson. We want a whole new world economic order based on justice. We want higher prices for our exports, and different terms of trade. We want control over multinational corporations. The clash between the superpowers and newly independent countries exposes some fundamental characteristics of General Assembly discussions in this period. Sometimes they harmonized with external events and sometimes they ran counter to them, but they always reflected Cold War dynamics (Interview with Richard Gardner, Columbia Center for Oral History Archive 12, as cited in Lorenzini, 2019, p.89).

Considering Wachuku’s response and drawing on Victor Turner’s theory of liminality (being in a transition stage or between) and Gregory Bateson’s concept of schismogenesis (a process of differentiation or conflict), this paper focuses on Iran as a case study to illustrate that the development slogans are used upon so-called “developing” and “underdeveloped” nations by powerful states and/or through their institutions enabling the so-called “developed states” to exercise power over the rest of the world.

Schismogenesis and Liminality

In his anthropological study of a certain ceremonial behaviour, Bateson (1936, p.175) defines schismogenesis ‘a process of differentiation in the norms of individual behaviour resulting from cumulative interaction between individuals’ and he identified two types schismogenesis: the one symmetrical and the other asymmetrical (complementary). In symmetrical schismogenesis, the relationship between the parties to the interaction becomes progressively more competitive, such as the US-Russia nuclear arms race. In asymmetrical schismogenesis the relationship between both parties tends towards a complementary fit, such as the growing gap between rich and poor or schismogenesis between the dictator and his officials and/or people that is the process whereby dictators are pushed towards a state which seems almost psychopathic (Bateson, 1936).

In the last two centuries, the schismogenic processes that has occurred between states, between states and their officials, between religious groups and even between individuals, have resulted in a destructive and pernicious war as well as revolution and terror (Isaloo, 2017). A complementary schismogenesis “illustrates very clearly how the megalomaniac or paranoid forces others to respond to his condition, and so is automatically pushed to more and more extreme maladjustment” (Bateson, 1936, p.186). This type of schismogenesis was experienced in various societies until now (Horvath & Thomassen, 2008). When a schismogenic process starts, suddenly the normal and peaceful relations between two or more states, bodies, parties and leaders transform into an environment full of conflict, and as a consequence a liminal phase begins (Isaloo, 2017).

Liminality refers to any situation or object being ‘betwixt’ and ‘between’; a transition period, an inter-structural situation and process moving from one stage to another (Turner, 1967, 1982). The transitional stage, as a liminal moment or period, is a temporary break off from normal, daily and everyday activities. Thus, liminality is inconsistent with ordinary day-to-day life. If this break becomes unlimited, a prolonged or a permanent liminality takes place. As Szakolczai (2000) explains, the term enables us to perceive the way in which uncertainty can emerge and helps us to find answers to questions such as: why and how such liminal periods can be used and even artificially provoked? (Szakolczai, 2013). In liminal periods encompassing war, revolution and crisis, political actors can use symbols, images, signs, narratives, words and rhetoric to manipulate and control the crowd to reach their pre-planned goal. The same method is used by the US, Russia, China and other powerful nations to wangle, fudge and misrepresent, but in contrast to classical liminal situations, whereby society stands at the threshold of transition for a limited time, this period now seems to be prolonged or maybe permanent.

Development and world powers

According to Potter et al. (2008, p.22) development derives from the 19th century ideal of progress and it is ‘a historical process of change which occurs over a very long period’ which is used as a carrot to contribute to political goals of the developed nations, particularly the West, during the 20th century. As Esteva et al. (2013, p.261) point out, if you live in Rio or Mexico City today, you need to be very rich or very numb to fail to notice that development stinks’. In other words, development is an idiom that converted the modernisation of the “developed nations” into a universal model of and yardstick for social change, which was then imposed upon nations in the Global South through powerful institutions predominated by “developed nations”, thus enabling the Global North to exercise power over the Global South and to erase their specific character (Rahnema & Bawtree 1997, Nilsen 2016).

The Cold War between the West and the East (the Soviet Union) significantly complicated the development process and divided the world into two opposing camps, Capitalism and Communism. The West feared that socialist ideology was more appealing to newly emerging states in the Global South and they, particularly the US, became concerned that as countries were achieving independence in the Global South, they were being attracted towards the Soviet Union. Therefore, the US took undercover military action to destabilise states and governments that showed a tendency to join the Soviet Bloc and also launched more overt development programmes. These operations, particularly military operation, held most of the US targeted nations in liminality and created a schismogenic process. Countries targeted by the Soviet Union, such as Afghanistan, experienced the same liminal condition, destructions and uncertainty.

Despite friendly relations between the US and Russia in the beginning years after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russian leaders were concerned about projects of regional cooperation and West-supported free market, which meant for Russian leaders nothing but efforts with a delicate cover of neo-imperialism to plunder its valuable raw materials, particularly from the middle of 1990 (Dash, 1999). Some politicians such Yugeni Perimakov (in 1996) were obviously concerned that Russia would play the role of a great power and wanted Russia’s relations with the West to be based on a fair cooperation as well as mutual advantages (ibid).

After the Cold War, the West and Russia had some cooperation. For instance after the 9/11 period, Russia assisted the US in the first phase of the war in Afghanistan by providing information, and in 2008 the US and Russia cooperated on arms control in some countries such as Afghanistan and Iran. Accordingly, there were new arguments after the end of the Cold War between the US and Russia, but relations between them had deteriorated when Putin claimed that Hillary Clinton had been behind the demonstrators who had protested his return to power in 2012. The next year, Putin granted political asylum to Edward Snowden (the NSA contractor who leaked classified documents and fled to Russia) and rejected the US request to return him. Their relations deteriorated further in 2014 when the West supported protests against the pro-Russia Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych and the annexation the Crimean Peninsula by Russia. The Schismogenic process between the West and Russia created a conflict in Ukraine and left the whole society in prolonged liminality. The operation of the West and Russia in Ukraine not only destroyed the economy and killed many innocent people, but also divided the country. The West and Russia have imposed a similar schismogenesis in the Middle East (i.e. Syria) and maintained it in a prolonged liminal stage where we can witness destruction, extermination, disorder and massacres rather than any type of development.

Iran and world powers

Over the past four decades, the US, Russia and China have played a significant role in Iran's international relations and behaviour. The EU member states’ discussions on whether to continue cooperating with Iran, despite disagreement by the US, has turned into an identity question in Europe. Thus, Iran-US conflicts are more multilateral than bilateral and their relation cannot be explained without taking the role of Russia, China and the EU member states into consideration. For example, in recent years, the issue of Iran’s accessibility to nuclear weapons was a sword of Damocles on Moscow-Tehran relations. Particularly, the US intention to limit Iran’s nuclear and technological capabilities, which is supported by its allies, has greatly overshadowed the cooperation between Iran and Russia. The JCPOA (The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action), signed by Iran and several world powers or the P5+ (China, France, Russia, United Kingdom, United States—plus Germany) in 2015, placed significant restrictions on Iran’s nuclear program in exchange for sanctions relief. In 2018 President Trump withdrew the US from the deal, claiming it failed to curtail Iran’s missile program. Now, in 2021, President Biden claims that the US will return to the JCPOA if Iran resumes its compliance. On 6 March 2021 Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs Simon Coveney has travelled to Tehran to meet with the Iranian president Hassan Rouhani for discussions on the stalled nuclear deal. As a result, the P5+ are now (1st May 2021) attending a meeting at the Grand Hotel of Vienna as the try to restore the deal. In fact, the US sanctions against Iran, which started after the 1979 Islamic revolution and reached its highest level during the Trump administration, have firstly kept more than 80 million Iranians in a liminal position for about 42 years, secondly created other schismogenic processes in the Middle East and in the entire planet, and thirdly led Iran to establish close relations with Russia and China.

The West, particularly the US, plays a decisive role in the diplomatic relations between Iran, Russia and China. During the last decades the relations between Iran, China and Russia in the military, economic and energy sectors met with a sharp and negative reaction from the West. Particularly after the 2015 cooperation between Iran and Russia in Syria, the West attempted to decompose any convergence or unity between these two countries. Thus, studying the position of the relations between the US, Iran, Russia and China in global policies can specify their position in the current age. After the 2014 conflict between the West and Russia, the China-Russia relationship became stronger and their pragmatic strategic partnership extended further. ‘After the European Union and the United States imposed sanctions on Russia, President Vladimir Putin made a dramatic turn to China and signed a series of deals, including a $400 billion deal to export gas to China last May’ (Gabuev, 2015, p.2). As a global actor, China is increasingly wielding influence across a wide range of key strategic and geographic domains. This schismogenic process between the US and Russia (and China) provided Iran with a strategic opportunity to join two powerful states (Russia and China) and to be able to manoeuvre against US threats and sanctions.

After the 1979 revolution, Iran adopted a foreign policy based on rejecting both the West and the East under the motto ‘neither East nor West’. But after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the beginning of a new international system and relations, Iran’s foreign policy changed and showed a tendency to form coalitions and a policy of unity instead of a policy of rejection and avoidance. Although the antagonistic policy toward the US continued, Iran tried to achieve a strategic cooperation with America’s rival powers such as Russia and China to expedite its oppositional foreign policy. In fact, US international policies have driven Iran closer to Russia and China. Today, Russia and China effectively shelter Iran from complete isolation and provide it with political support, defence assistance and economic ties that it cannot receive elsewhere. As a result, Russia and China serve to deter Western efforts to pressure Iran. Doing so affords the two powers the ability to poke the west, and the US especially, in the eye, while providing the access to an important market and granting ties with a critical regional player with access to key resources (Tabatabai and Esfandiary 2018). This does not mean that Iran can get everything from China and Russia. For example, instead of working on agricultural, environmental and economic development in Iran, Russia is very much interested in expanding arms and weapon sales. The same is true for the US role in the Middle East.

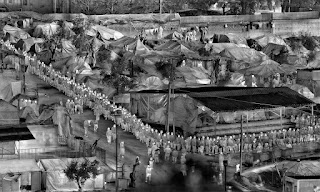

The major world powers (the US, Russia, China, EU member states and the UK after Brexit), who are also the major arms suppliers in the Middle East, have transformed the Middle East to one of the most heavily armed regions in the world, featuring numerous schismogenesis and liminality that involve many states in the region. For example, ongoing schismogenesis and liminality in places like Iraq, Afghanistan, Yemen, Syria, and Libya are justified by employing images and rhetoric of democracy, security and development. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) data, which illustrates arms suppliers to the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), the US has supplied nearly 45% of the arms imported by Middle Eastern states between 2000 and 2019, while Russia accounted for 19%, France for 11.4%, the UK for 5.8%, Germany for 3.7% and China for about 2.5%. Indeed, weapons sold by the major world powers have usually empowered totalitarian regimes that repress human rights, fostering political instability that is even characterized as a threat to arms suppliers’ interests. The significant question is: Why do they continue arms sales? This question was simply answered by President Donald Trump on October 20, 2018, at Defense Roundtable (White House) by arguing that new arms sales to Saudi Arabia would be worth “over a million” jobs for the US. This obviously demonstrates that first, the major world powers are not interested in the development of the Middle East and second, how developing and underdeveloped countries send trillions of dollars to developed countries rather than the other way around (see Hickel, 2017).

Conclusion

The current international relations and system is designed to protect the interests of powerful states. All developing and underdeveloped nations are directly or indirectly forced to follow the political and economic interests of one or more of the powerful or developed nations to be able to survive. In other words, only the major world powers benefit from the existing system and some of them obviously operate and behave as dictators in the current international relations.

To build a peaceful life for everyone in the whole world, the developed countries must free the developing and underdeveloped countries and help them to exit liminality by encouraging them to spend their money on development instead of buying weapons. Otherwise, the whole world will witness further schismogenesis and liminality. Remaining in liminality will create new schismogenic processes and will lead us to a new crisis. We know how to fix the problem and how to develop other parts of the world. Development of any single nation will benefit all of us in the long term. To build a better life in our planet, we must develop broad cooperation with all nations abiding by the principles of equality and mutual benefit.

Bibliography

Bateson, G. (1936). Naven: A Survey of the Problems Suggested by A Composite Picture of the Culture of a New Guinea Tribe Drawn From Three Points of View. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dash, P. L. (1999). Rise and Fall of Yevgeny Primakov. Economic and Political Weekly, 34(24), 1494-1496.

Esteva, G., Babones, S. J., & Babkicky, B. (2013). The future of development: a radical manifesto. Bristol: Policy Press

Gabuev, A. (2015). A “Soft Alliance”? Russia-China Relations After the Ukraine Crisis, the European Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved from https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/188414/ECFR126_-_A_Soft_Alliance_Russia-China_Relations_After_the_Ukraine_Crisis.pdf

Hickel, J. (2017, January 14). Aid in reverse: how poor countries develop rich countries. The Guardian. Retrived from https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2017/jan/14/aid-in-reverse-how-poor-countries-develop-rich-countries

Horvath, A. and Thomassen, B. (2008). ‘Mimetic Errors in Liminal Schismogenesis: On the Political Anthropology of the Trickster’. International Political Anthropology, 1(1), 3-24

Isaloo, A. S. (2017). Power, Legitimacy and the Public Sphere: The Iranian Ta’ziyeh Theatre Ritual. London; New York: Routledge

Lorenzini, S. (2019). Global development: A cold war history. Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press

Nilsen, A. G. (2016). Power, Resistance and Development in the Global South:Notes Towards a Critical Research Agenda. Int J Polit Cult Soc, 29, 269–287

Pankhurst, J. (2012). Religious Culture: Faith in Soviet and Post-Soviet Russia. In Dmitri N. Shalin, 1-32. Retrieved from https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/russian_culture/7

Potter, R. B., Binns, T., Elliott, J., Nel, E. & Smith, D. W. (2017). Geographies of development: an introduction to development studies. 4th edition. Abingdon: Routledge

Rahnema, M., & Bawtree, V. (1997). The post-development reader. London: Zed Books

Szakolczai, A. (2000). Reflexive Historical Sociology. London; New York: Routledge

Szakolczai, A. (2013). Comedy and the Public Sphere: The Rebirth of Theatre as Comedy and the Genealogy of the Modern Public Arena. London; New York: Routledge

Tabatabai, A. and Esfandiary, D. (2018). Triple-Axis: Iran's Relations with Russia and China, London. New York: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd.

Turner, V. (1967). The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. New York: Cornell University Press.

Turner, V. (1982). From Ritual to Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play. New York: PAJ Publications.

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Dr Amin Sharifi Isaloo

Department of Sociology and Criminology

University College Cork

Comments

Post a Comment