Vertical Verse: Aerial Maps of the Middle East in Contemporary Irish Poetry.

By Natasha Remoundou

This blog article explores the ways technological media of vertical and oblique war photography and military surveillance are captured in contemporary Irish poetry to open up discussions about the Western 'gaze', ways of 'seeing'/'mapping', mobility, and conflict in the Middle East.

In the photographic series ‘Heat Maps’, Irish conceptual documentary

photographer Richard Mosse documents a digital atlas that archives forced

mobility across the globe while capturing in film a haunting parallel journey

between spectators and those that remain ‘unseen’ from above and afar. By means

of repurposing military surveillance technology, Mosse uses vertical and

oblique mid-wave infrared camera techniques, commonly used to detect and track

criminals, to photograph humans in states of exception and landscapes in ruins.

The specific use of this apparatus of visual surveillance assembles the

transcontinental trails of migrants from Africa and the Persian Gulf to Europe

across land and water to tell multiple stories of displacement. Moreover, this

lateral crossing is registered through an invisible, hovering gaze that

simulates the feasibility of ‘domination at a distance’[1]

while recording evidence.

The shadowy optical effects elicited from this special mode of remote sensing images for military operations heavily relies on thermal detection that captures the contours of bodily temperature in the dark and renders it visible from miles away. The stills depicting black and white dioramas of twenty-first century refugee traversals in aquatic ribs or on foot, evoke obscure eighteenth-century engraved illustrations or Victorian daguerrotype-processing methods. Oftentimes, the visual after-effect procured by limited visibility and classification is tied to notions of entrapment reminiscent of thermal imaging techniques used for hunting and monitoring wild animals. As Andrea Brady argues, this type of remote control technology in conjunction with the ubiquitous ‘overhead shot’ hinders both ‘an exchange of the gaze’ and ‘empathy’ while encouraging the use of force.[2] I want to consider the ways through which these critical challenges foregrounded in artworks like Mosse’s digital photography can be applied to poetry. While they fix the perceiver’s gaze from a vantage point of reference looking down on the target as a candidate for imminent contingency, the visceral aerial dioramas of refugee routes across land and sea that culminate in detention centres, in camps of the West, or in the sea, replicate and embody the poet’s eye. This article considers the aesthetic and political economy of vertical and oblique photography and their impact in contemporary Irish lyric through the poetry of Deirdre Brennan and Michael J. Whelan, respectively, and the ways their works respond to the wars in Iraq and in Syria. By revisiting the problematic of ways of vertical seeing in poetry via the perspective of overhead technoscience of weapons and machines of mass destruction, the poetic vision is superimposed against the surveillance agent troubling the figure of the objectified, hunted down subject.

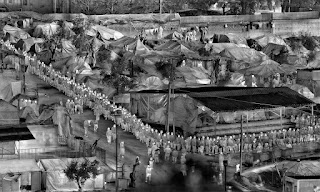

Detail of “Moria in Snow,” 2016. ©Richard Mosse.

Richard

Mosse, Larissa Camp, Greece,

2016. ©Richard Mosse.

My analysis investigates the ways poetry functions critically beyond a merely aesthetic, material two-dimensional map of representation. Departing from notions of the poetic vision as an aerial artwork that is set vertically (or obliquely) from ‘above’ in military surveillance contexts rendering these journeys obvious, intelligible, and ‘seen’, this critical alliance between poetry and photography rather seeks to bring figurations of geopolitical and ethical distancing, proximity, intimacy, and survival into sharper focus to perform a critique of aerial imperialism and domination. Echoing the force of multispectral imaging and sonar sensors, the poems read here, in other words, use tropes of aerial warfare and military technology to look at what takes place down ‘below’ and far away on the surface of the earth or the seas beneath our feet. These downward strata of observation of environments of destruction from a perceived rim of the atmosphere, expand the horizon of what becomes visible (and thus intelligible). In the trajectory between ‘above’ and ‘below’, this bifocal spectrum constructs a radical poetic perspective that opens up critical debates on contemporary geographies of inequality, rights, and traversal in writing.

Exploring the motif of descent through landing, the poems at the focus of this study examine -along with notions of mobility and flight- the mechanisms of power, othering, and belonging against the backdrop of the catastrophic effects of contemporary military politics precipitated by invasions of civilian airspaces, privacies, and lives. Set in site-specific urban landscapes from Aleppo to Baghdad, the poems recalibrate the power of the lyric in so far as they problematize ideas of agency, and privilege. This is poetry that portrays reality from the viewpoint of the omniscient/omnipotent western observer raising questions about the relationship between poetry and empathy.

Accordingly, Deirdre Brennan’s short lyric poem 'Oíche

Arabacha'/ ‘Arabian Nights’ carves out a kaleidoscopic

vista of aerial imperialism and military aggression by having the disembodied

voice/eye of the speaker suspended over a split image projecting the ruins of

present-day Babylon. Confronted with the sight of material devastation past and

present, of humans and landscapes, the poem threads together gradient

geographical loci where counterinsurgency military operations from the western

front precipitate swift aerial assassinations and planetary annihilations

against all others. In the final stanza of three, the speaker observes:

|

Ancient sites are levelled as landing sites for helicopters. Thousands of bags are stuffed with old bones, bits of old pottery bricks prised out from triumphal arches thrown aside for clearance one with cuneiform inscription – |

Láithreáin ársa leacaithe, ina n-ionad tuirlingthe ingearán anois, na mílte mála gainimh stuálta le cnámha, blúirí seanphotaireachta brící tochailte as áirsí mórshiúlacha caite ar leataobh i gcarn carta, inscríbhinn dhinghruthach ar

cheann amháin –[3] |

Alongside the historical remnants of former civilizations, empires, and dynasties left in contemporary ruins, the poem looks back and at the same time ‘overhead’ in order to retrace and decipher a history of colonial western violence that does not seem to have abated. At the mercy of time, natural elements, and sovereign power, the panoptic visuality of the archaeological site of Babylon is now turned into a spectre of an endless cultural and environmental barbarity due to the war, where, as Walter Benjamin argues, ‘we perceive a chain of events’ and see ‘one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage.’[4]

Still from a GoogleEarth satellite image of ancient Babylon. ©Google

In

so far as the poem bears witness to the asymmetry of colonial warfare

juxtaposed to the immanence of the war on terror, the poem readily undercuts

what Mai Al-Nakib terms the ‘cursory

archaeology of our planetary ruins’[5] collapsing spatiotemporal borders. Before

Brennan invites readers to zoom in on the salvaged engraved cuneiform tablet still

standing amid the safe space of poetry, the ravaged Babylonian site encompasses

the record of perpetual strife and protracted devastation since time immemorial.

The poem references the imperial ruthlessness of such controversial historical

figures as Xerxes, Darius, and Alexander, and concludes with Nebuchadnezzar

refracting the idol of the oppressor back at the (Western/ English-speaking)

viewer. Originally written in the Irish language and then translated into

English, the poem unveils also legacies of linguistic abjection to further a

wider postcolonial gaze back at transnational histories of oppression and

disenfranchisement. In this light, it also enacts a critique of western

capitalism and neoliberal democracies, while meditating on the role of poetry

to shape global alliances. In the first stanza, the optic spectrality top-down blurring

the demarcating line between perpetrators and victims, poet and reader,

interpellates the hyper-exposure of the subaltern against the proliferation of

aerial technologies of violence:

|

An oily

mist hangs over cities, over

groves of date palms, pomegranate

and tamarisk, night

after night aeroplanes

whine their

lullaby to children… |

Ceo

bealaithe olúil Ar

foluain os cionn cathracha, Os cionn

pailmeacha dátaí, pomagránaití

is tamaraiscí, oíche i

ndiaidh oíche geonaíl

na n-eitleán ina suantraí do pháistí …[6] |

In the same manner, the poem remains attuned to the sonic force of

flight as a method of surveillance, punishment, virtual (albeit protected)

immediacy and noise. What is ‘seen’ is

also ‘heard’ vertically resounding quotidian visualisations of ‘other(ed)’

scenes of carnage in zones far away from the collective western consciousness,

somewhere where the ‘voice of the muezzin’ has now been silenced via

technologically advanced airstrikes in live, graphic transmission:

|

people

sliced with exploding shells lie dead

under the rubble of houses, corpses

piled in mortuaries and freezers wait for

relations to claim them. |

Daoine

gearrtha ag smionagar sliogán, adhlactha

faoi mhionrabh a dtithe; coirp ar

mhuin mhairc a chéile i

marbhlanna is reoiteoirí ag

feitheamh ar dhaoine a

mhaífeadh gaol leo.[7] |

Interrogating notions of the inclusive and exclusive ‘us’ versus all others, planetary catastrophe and human control over nature (and over other humans), the poem ‘Rib’ by Michael J. Whelan, reiterates the troubling ethical currency sustained by the fantasy of military executions from above against innocent civilians. Included in his poetry collection Rules of Engagement that was published in 2019, Whelan’s work pays homage to the centenary since the start of the Irish Revolution (and more than a century after the Great War of 1914-1918), but also to the Irish War of Independence and the Anglo-Irish War. Whelan, however, examines notions of memory and conflict through the spectrum of war from Ireland to Syria, from the West to the East, based on his own experience as a United Nations peacekeeper in Lebanon and Kosovo with the Irish Defence Forces [8] and curator of the Irish Air Corps Military Aviation Museum. Throughout the collection, the central, autobiographical figure of an Irish poet-soldier in search of truth and meaning in a world torn apart, compels him to explore other poetic voices from the past while striving to reconcile the self against natural and human catastrophe at a transnational, global scale.

Here, too, the incorporeal utterances of the speaking ‘we’ cast a collective ‘eye’ down on the earth where very little has changed since the beginning of the twentieth century. ‘We see their journey,’ Whelan writes, ‘everyday we see them’ and the poem acts as a passive testimony of the complicit viewer/bystander. The short, sixteen-line poem then departs from the source of the pillaging while in flight, a recurrent motif in Whelan’s poetry. Subverting conventional notions of flight as an equivalent of freedom and exploration, the image of the gliding combat chopper methodically and indiscriminately dropping barrel bombs on the city of Aleppo is only one visual thread of a more complex web of associations connected to vertical military extermination. The rhetoric economy of Whelan’s lines highlights the speed of violence from above, a violence that serves as the apparatus of involuntary dislocation, uprootedness, and dispossession manifested in the figure of the fleeing survivor who is now compelled to navigate the Mediterranean archipelago without resources:

A

barrel bomb

dropped

form a chopper

tears

down a street in Aleppo,

the

survivors,

packed

into a rib

punctured

by barbed wire

on

the Mediterranean,

drown,

their children down.[9]

The final lines of the short lyric move from an aerial vantage to

the ground and on the surface of the sea in an emergency landing operation

whereby persecution and exclusion are not implied but persist. The

technoscientific supremacy of the military chopper replaced by the flimsy rib

bears a metonymic signification for the perilous and often terminal

sea-crossing itinerary of the uprooted.

An aerial view of the buildings destroyed in the Tariq al-Bab neighbourhood in Aleppo.

Photograph: Anadolu Agency/Getty Images. Source: The Guardian, October 11th,

2016.

We

see their journey,

where

it begins- where it ends,

their

shoes washed onto the sand,

behind

the beach there is barbed wire too.[10]

The poem emphasizes not just the fundamental disjuncture between

‘us’ and ‘them’/others, citizens and non-citizens, West and East, oppressors

and oppressed. The repetitive viewpoint

of the self-policing and omnipresent gaze of the sympathizing spectator

habituated to the insistent banality of expulsion,[11]

serves as a metaphor for the substitution of the use of brutality with the gaze

of empathy:

Every

day we see them,

every

day a rib waits in the rubble,

every

day the same commiserations

from

the West.[12]

While Whelan’s and Brennan’s poems could not be more damning of states and policies of exclusion perpetuating cycles of abjection as if through a seeable regime, they can be read as calls to resist what Bruno Latour indicates the ‘loss of a common orientation’:

We shall have to come down to earth; we shall have to land somewhere. So, we shall have to

learn to get our bearings, how to orient

ourselves. And to do this we need something like a map of the positions imposed

by the new landscape within which not only the affects of public life but also

its stakes are being redefined.[13]

The impulse to combat the possibilities of such an undoing Latour

refers to, is perhaps contemplated here in a vertical poetics of ‘common

orientation’ (and common visibility), whereby both Deirdre Brennan and Michael

J. Whelan attempt to meditate on a rethinking and a disclosing of antinomies of

power and rights from the side of those inflicting regimes of rightlessness.

Against such old and new landscapes of geopolitical exclusions, Irish poetry

catches a glimpse of ‘unseen’ lives and cartographs them up close behind the

safe space of the distant spectator’s retina.

[1]

Bruno Latour, Science in Action.

Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1987: 223.

[2]

Andrea Brady, ‘Drone Poetics’. In New

Formations: A Journal of Culture/ Theory/ Politics. Vol. 89-90, 2017: 118.

[3]

Deirdre Brennan. Cuislí

Allta/ Wild Pulses: Rogha Dánta/ Selected Poems (Galway:

Arlen Press, 2017): pp. 140-141.

[4]

Walter Benjamin. ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’. In Illuminations. Trans.Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken Books, 1969:

249.

[5] Mai Al-Nakib, ‘In Ruins: Reflections beyond Kuwait.’ July 7, 2021: https://www.worldliteraturetoday.org/blog/essay/ruins-reflections-beyond-kuwaitby-mai-al-nakib

[6] Deirdre Brennan. Cuislí

Allta/ Wild Pulses: Rogha Dánta/ Selected Poems (Galway: Arlen Press, 2017): pp. 140-141.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Michael Whelan, Peacekeeper, Doire Press, 2016. Whelan,

who was posted to the Irish Air Corps at Casement Aerodrome in Baldonnel, has

also served as an infantry soldier, signal operator, and aircraft maintenance

technician, and was awarded the 2010 Paul Tissandier Diploma by the Fédération Aeronautique Internationale

for his work in preserving Irish military and aviation heritage.

[9] Michael Whelan, Rules of Engagement (Inverin: Doire Press, 2019): p. 66.

[10]

Ibid.

[11]

Saskia Sassen, Expulsions: Brutality and

Complexity in the Global Economy. USA: Harvard UP, 2014.

[12] Michael Whelan, Rules of Engagement (Inverin: Doire Press, 2019): p. 66.

[13] Bruno Latour, Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime. Trans. Catherine Porter. Cambridge: Polity, 2018: 2

Comments