Consociation and the Upcoming 2022 Lebanese Parliamentary Elections

|

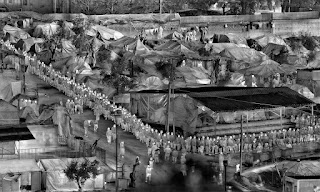

Sunday of Unity Protests, 3 November 2019. Photo by Katarzyna Wodniak. |

On 17 October 2019, Lebanese citizens from various sects began protesting en-masse under the slogan “killun yaani killun” meaning in Arabic “all of them means all of them”. By “them” the protesters were referring to the political class and sectarian leaders that have been ruling Lebanon since the end of the civil war in 1990. While the protests had been attributed to a WhatsApp tax imposed by the government, it was the inability of Lebanese citizens and residents of Lebanon to withdraw normally from their bank account deposits in US Dollars that caused an aggravated state of alarm among the various populations of Lebanon. The acute and ongoing economic crisis that Lebanon has been enduring since late 2019 has been described by the World Bank as possibly one of the worst three economic crises worldwide in the past 150 years. With the drastic devaluation of the local currency, the Lebanese Lira, the middle class has been almost wiped out in a previously middle income country where now over 70% of the population are living under the poverty line.

The October 2019 protests dwindled by March 2020, yet parliamentary elections are scheduled for 15 May 2022 - so will the Lebanese people vote out the current leaders? The protesters, as well as many in the international community, believe that this crisis is mainly the result of decades of corruption and mismanagement on the part of the political class. For the Lebanese people, this is actually not a recent “discovery” as the corruption of the political class is routinely discussed in public discourse, even prior to 2019. However, the same sectarian leaders have been re-elected by the majority of Lebanese voters since the first post-civil war parliamentary elections in 1992 and until the last parliamentary elections in 2018.

While this re-election pattern may seem puzzling, one can find explanations in the political arrangement of Lebanon centred on a consociational or confessional system. Consociation, first theorized by Arend Lijphart, is a political system designed to manage conflict by sharing power in multi-ethnic or multi-sectarian societies, and this has been the political system the Lebanese state adopted since independence in 1943. Under the Ta’if Accord of 1989, Lebanon’s post-civil war constitution, Lebanon remained a consociational democracy where the president continued to be a Christian Maronite, the prime minister a Muslim Sunni, and president of chamber of deputies is now held by a Muslim Shia. Additionally, parliamentary seats and top jobs in governmental institutions are divided equally between Muslims and Christians.

With this context in mind, one can draw on the work of Asim Mujkic on the Dayton Accords in consociational Bosnia-Herzegovina for parallels. Mujkic accurately delineates that members of sectarian communities do not vote for lower taxes, an improved welfare state and so on, but rather they vote based on their sectarian identification for the survival of the group, as it ensures their own survival. Moreover, when it comes to elections in the Lebanese consociational system, sectarian allegiance is also reinforced by prevalent and pervasive clientelism. Within a patron-client relationship, voters are bound to the political leader or political party by a network of transactional ties, whereby economic resources, government jobs, and social services are distributed to the clients in exchange for political loyalty that translates into voting for those political leaders and parties as well as their allies in parliamentary elections.

Whether the reign of the sectarian system holds in the 15 May 2022 elections remains to be seen. These elections will involve the usual competition between the various traditional sectarian political parties, but also candidates belonging to alternative opposition parties and groups predating or born out of the October 2019 revolution as they refer to it. These oppositional groups and parties mainly present themselves as centre-left or social democratic, with demands for a secular state, fairer distribution of wealth and social services, but also mostly state monopoly over weapons, with a direct reference to the weapons of the Shia militant group Hezbollah.

The calls for a secular state actually date back to the Ta’if Accord. Some analysts partially attribute the cause of the Lebanese civil war that broke out in 1975 and lasted until 1990 to the sectarian system and an imbalance of power due to changing demographics between Lebanese Christians and Muslims. Therefore, the Ta’if Accord was originally agreed upon as a transitional document that will ultimately lead to deconfessionalization. However, it did not set a time limit nor a time-frame to this transitional period. It also did not stipulate that the recommendations of the committee entrusted with deconfessionalization are binding neither to parliament nor the executive. The committee that was due to be established following the election of the first post-Ta’if parliament never materialized.

Following the upcoming elections - if they are not postponed due to disagreement among the traditional political parties as some observers are warning - Lebanon is faced with two scenarios. Precisely, either the consociational arrangement will continue with the domination of the traditional political parties, or the journey towards a secular, non-sectarian state will initiate with the alternative opposition parties, if they commit to their declared electoral objectives. Both of these scenarios come with their challenges. If the traditional parties win the elections, there will be difficulties in terms of agreeing and implementing reforms needed to escape the crushing economic crisis within a power-sharing arrangement that often causes delays and at times paralysis in government action. These reforms are in fact a prerequisite for receiving much sought-after loans from the World Bank.

On the other hand, if the alternative opposition candidates win the elections, the Lebanese political system structured around sectarian belonging would need to be reworked on secular foundations, with the implications that has for the political power of various Lebanese sectarian groups in a country where the population has shifted to a Muslim majority since the 1970s. Moreover, one can reasonably expect acute tensions between the Lebanese state and Hezbollah around the possession of weapons outside the confines of the state. Additionally, the question arises whether the legal exclusion of minorities because of their position within the sectarian system, such as Palestinian refugees, will change?

While some observers attribute many of the challenges faced by Lebanon over the decades to the sectarian system, sectarianism in Lebanon is not a given but rather a modern phenomenon that emerged in the 19th century. As elucidated by the work of Ussama Makdisi, although the civil war of 1860 between Christian Maronites and Muslim Druze is most commonly cited as the root of sectarianism in Lebanon, it could be more accurately traced back to 1841. Despite Ottoman rule over Lebanon, the violence of 1841 allowed for intense interventions by France and Great Britain in the affairs of Mount Lebanon and indirectly the Ottoman Empire. These powers were deeply concerned with restoring order and harmony between the two communities and consequently the European powers proposed partition. The European designed partition plan took it for granted that there were two distinct and primordial tribes of Christians and Druze and that all inhabitants of Lebanon adhered to one or the other.

Partition in the 19th century had profound effects leading to the categorizations of either Druze or Christian. Since then, religion has been the most important form of political identification. However, the local inhabitants and precisely the elites were not agentless victims in the process of sectarian identity formation. Instead of resisting their representation by the dominant powers as primordial sectarian communities, local elites used to their advantage these powers’ concerns for re-establishing order by presenting themselves as the genuine representatives of such sectarian communities. Both Druze and Maronite elites worked towards transforming their religious communities into political communities. This sectarian identification was carried onto an enlarged Lebanon which included more sects since 1920, such as the Muslim Sunni and Shia.

In light of this modern history of Lebanon, the upcoming Lebanese elections are unlikely to rid Lebanon of entrenched sectarianism in the short or possibly medium range, but they do present the opportunity to dismantle, or begin to dismantle, the consociational system and decolonize sectarian categories which some observers consider to be responsible for Lebanon’s misfortunes. The catalyst may be the economic crisis that has severely affected Lebanese from all religious sects without exception and has certainly caused disillusionment with the sectarian leaders among segments of the Lebanese population.

Further Reading

Baaklini, Abdo I. 1983. Ethnicity and Politics in Contemporary Lebanon. In Culture, Ethnicity and Identity. W. McCready, ed. New York: Academic Press.

ESCWA 2021. Lebanon: Almost Three Quarters of the Population Living in Poverty. Available at https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/09/1099102

Ghosn, Faten and Khoury, Amal. 2011. Lebanon After the Civil War: Peace or the Illusion of Peace? Middle East Journal, 65(3).

Haddad, Simon. 2002. Cultural Diversity and Sectarian Attitudes in Post-War Lebanon. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 28(2):291-306.

Hamzeh, A. 2001. Clientalism, Lebanon: Roots and Trends. Middle Eastern Studies 37(3):167-178

Harik, Judith P. 1998. Democracy (Again) Derailed: Lebanon's Ta'if Paradox. In Political Liberalization and Democratization in the Arab World Vol. 2. B. Korany, R. Brynen, and P. Noble, eds. Colorado; London: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Hudson, Michael C. 1997. Trying Again: Power-Sharing in Post-Civil War Lebanon. International Negotiation 2(1):103-112.

Lijphart, Arend. 1969. Consociational Democracy. World Politics, 21(2), 207-225.

Makdisi, Ussama. 2000. The Culture of Sectarianism: Community, History, and Violence in Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Lebanon Berkeley, Calif.; London University of California Press.

Mujkic, Asim. 2007. ‘We, the Citizens of Ethnopolis’. Constellations 14 (1): 112-128.

Ofiesh, Sami A. 1999. Lebanon's Second Republic: Secular Talk, Sectarian Application. Arab Studies Quarterly 21(1):97-116.

Salem, Paul. 1998. Framing Post-War Lebanon: Perspectives on the Constitution of the Structure of Power. Mediterranean Politics 3(1):13-26.

Serhan, Waleed. (2019) Consociational Lebanon and the Palestinian Threat of Sameness, Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 17 (2): 240-259

About the author: Waleed Serhan is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Management at the University of Social Sciences, Warsaw. Waleed holds a PhD in sociology from Trinity College Dublin, the University of Dublin, and an MSc in development studies from the University of Glasgow. His research interests are in the areas of migration, race and ethnicity, and ethnic conflict with a focus on the Arab region and Europe. Previously, he was a researcher and project coordinator on one of the widest scale museum audience research projects in the Arab Gulf region based at UCL Qatar.

Comments

Post a Comment