Hiwa K’s Geopolitics From Below

|

| Do You Remember What Are You Burning? (2011) (by author) |

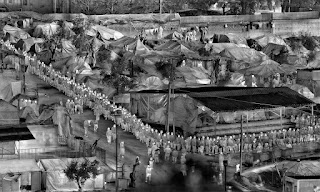

The first Irish exhibition by Kurdish artist Hiwa K takes its title from one of the works on display. Titled ‘Do you remember what are you burning?’ (2011), this work shows a group of people busy with burning the words of books they hold in their hands using a magnifying glass. The fierce sunrays of Sulaymaniyah, in Iraqi Kurdistan, burn and ‘smoke away’ the ink. The act of burning words is a powerful metaphor to explain a concept that political scientists have variably called façade or backsliding democracy, with the most radical ones explaining that neoliberal governance is indeed a potent vehicle through which democracy is weakened to the benefit of the few. In a recorded conversation with the curator, Hiwa K explains that in the past authoritarian leaders used to burn books, but today, they do not need to engage in such a symbolic act to defeat democracy. It suffices to burn the content of books, the printed words, to prevent people from discussing and practicing democracy from below, restricting their possibility to engage with each other meaningfully. The artist explains that this performance was staged in reaction to the repression of the 2011 protests which, according to Hiwa K, signalled an important turning point for the population of Sulaymaniyah, who realised that the promised democracy was perhaps ‘kinder’ than the previous regime – it burns words instead of books – yet it is equally afraid of autonomous and grassroots political action, hence the repression.

This short introduction helps clarify one of the most interesting aspects of Hiwa K’s work, that is his commitment to talk about geopolitical issues through metaphors and the everyday life. The totality of his work goes well beyond this and interrogates a number of different realms of human action, but the fil rouge connecting the works included in the Dublin exhibition is ‘geopolitics from below’.

‘They All Come Back To Me’

‘The Bell Project (2014-2015)’ is another powerful work exemplifying, in a painful way, how geopolitics and globalisation work. The Bell Project’s first part was realised in Sulaymaniyah and then completed in Venice. In Sulaymaniyah, Nazhad melted together bomb shields and other leftovers from weapons, tanks, and warplanes, while in Venice, in an historical workshop producing church bells but occasionally producing weapons too, the melted metals were shaped into a bell. As the bell was ready, a Catholic priest blessed it, following the tradition of ‘wishing the bell’ to call for joyful celebrations rather than warning the community against a military attack or other dangers. The cycle is complete: we follow the redemption of those metals – from causing deaths to being part of a bell in a country where no conflict is taking place. However, in spite of this sense of redemption, the Bell Project is deeply unsettling for the audience. Nazhad makes his living out of trading metals, which he obtains from collecting and reworking unexploded bombs and other weapons. It is a dangerous job, and Nazhad lost the use of a leg while doing it. Nazhad shows profound knowledge of every single piece he collects. For every item, he is able to name the country of manufacturing (Italy and Germany are often named), the army that used it and the war in which that kind of weapon was utilised. ‘They all come back to me’ is Nazhad’s bittersweet statement about the items he collects. He demonstrates a detailed and impressive knowledge of the global market of weapons and of how technological advancements have rendered some weapons more lethal or simply put them off the market. He also talks about the afterlife of those weapons, now turned into leftovers. For each piece of metal, in fact, there is a specific market and price, depending on the manufacturing of the weapon, the lethal quality of the gas or powder it contained, and whether some of that poisonous material is still present. Not only does Nazhad explain how globalisation works through the story of those weapons, but also how informal economies, often survival economies, rise and collapse after the rich have gotten richer and have left their poisonous leftovers to the poor.

The war is a constant reference in Hiwa K’s work. In ‘Qatees’ (2009), the artist’s attention to the everyday ways in which conflicts transform people’s life is exemplified. We follow Abbas, who is a constructor of antennas, a common activity during the Iran-Iraq war (1980-88) and other conflicts. The need to access information and the scarcity of electricity and working TV sets, have turned many people into experts of electromagnetics and broadcasting. To complete his antenna, Abbas utilises utensils such as spoons, scoops, wooden objects. In ‘My Father's Colour Period’ (2013), Hiwa K turns his attention to his family to explain the effects of the rapprochement between Saddam Hussein, the USSR and the West in the 1980s (the two blocs were in fact both supporting Iraq in the context of the Iran-Iraq war), and how much the Kurdish-majority areas were cut off from the rest of the country. As Soviet and Western money and technology started to circulate in Iraq, TV colour sets were introduced too, along with a brand new offer of movies from both Hollywood and the Soviet Union. Such TV colour sets, however, did not make it to Kurdistan. To make up for this absence, showing both stubbornness and an inventive spirit, the artist’s father, and the population in general, started to glue sheets of coloured cellophane to the screen of their TV sets. With new shades of colours, the black-and-white movies acquired new layers, new characters and dimensions.

‘Maybe vision is the last gift of God’

Hiwa K’s geopolitics from below could not avoid talking about migration, considering that the artist himself is a refugee who walked his way from Iraq to Europe to apply for international protection. In ‘Pre-Image (Blind as the Mother Tongue)’ (2017), the artist walks once again the whole road between Sulaymaniyah and what we understand being Italy, and he does so in a very peculiar way, that is, balancing on his nose a utensil made of steel and mirrors. Walking in this way catches the artist’s gaze in caged perspectives. While his head and eyes are turned towards the sky, Hiwa K’s gaze is immediately caught by the mirror, which force his gaze ‘down’ to either his own image or the tarmac of the road, as reflected in the mirrors. As the artist approaches Athens’ port and plans to illegally board a boat to his next destination (he’ll reach Italy), he is forced to wait for the right moment to attempt at boarding. This waiting time, which anticipates another, long, waiting time on the boat, means being unable to move, being hidden in a dark place where the eyes cannot see any light and, of course, it means no food, no water and no possibility for the body to find any comfort. The artist tells us about darkness, reflecting that when you see nothing, then your ears become your eyes (‘we become all ears’). ‘Maybe vision is the last gift of God’, Hiwa K wonders, anticipating the moment when the journey will be over and, with it, the darkness. The boat, the sense of being lost in darkness and confusion, and the selective enhancement of the senses remind us of Stephanie E. Smallwood’s book on the Middle Passage between the African and the American continents, Saltwater Slavery (2008). The confusion that accompanied the Africans’ experience of being abducted, forced to go to the United States and enslaved, was constantly accompanied by the sensorial experience of the salted water, which became a common item in the memory of the Middle Passage and became associated with that traumatising experience. By resonating with this, Hiwa K’s work too reminds us that the history of European nation states, like the history of the United States, is made of feelings and experiences of vulnerability, confusion, bewilderment, loss, dismay, desperation – regardless of the efforts to expunge them from the official historiography.

The topic of migration as a way to interrogate geopolitics prominently features in ‘View From Above’ (2017), too. In this work, we learn about the story of M, a Kurdish asylum-seeker who is to meet soon the judge making a final assessment on his application. M comes from a Kurdish-majority city which was declared a ‘safe zone’ by the UN, making M’s situation even more precarious. ‘The safe zone is fictitious’, Hiwa K explains, referring to M’s personal unsafety. Nevertheless, the safe zone is bureaucratically real, and especially so for the judge who’ll deliberate on M’s application. How to transform M’s condition from ‘being unsafe in a safe zone’ to ‘being unsafe in an unsafe zone’, the artist wonders? The solution M and the artist agree on, is to declare that M comes from another city, J, located by the UN in the ‘unsafe zone’. J is the city of M’s mother and M knows it: in fact, he used to spend the holidays there and has paid frequent visits to his extended family. He knows the city ‘from below’, Hiwa K tell us: he now needs to shift perspective, unlearn the city ‘from below’ and re-learn it ‘from above’, from a map. This is how bureaucrats in the UN and M’s judge know J – from a map, from above. By satisfying their standards and mimicking their power, M was able to convince them that, in fact, he comes from J, eventually obtaining the needed approval.

|

| View from Above (2017) (by author) |

The tragedy behind M’s success story is that thousands of people genuinely coming from J had to wait years before having their asylum applications approved, because they demonstrated they knew the city ‘from below’, thus not ‘fitting’ the preconceived knowledge of the decision-makers and the judges and making them suspicious. Hiwa K’s work is radically materialistic in both the use of metals, the attention to objects, and in its unveiling of the very real implications that abstract concepts (such as belonging, democracy, geography) have. In this sense, his geopolitics from below is very instructive and captures the ultimate ‘stuff’ theory (and art) is made of: not abstract and useless reflections for the ivory tower’s inhabitants, but the constant struggle to deconstruct this world and imagine another one.

About the author

Paola Rivetti is Associate Professor of Politics and International Relations in the School of Law and Government, Dublin City University. Currently, she is the chairperson of the Irish Network for Middle Eastern and North African Studies (INMENAS). She is the author of 'Political Participation in Iran from Khatami to the Green Movement' (2020). In 2021, she co-edited the special issue 'Revolution and Counter-Revolution in the Middle East and North Africa' published in the open-access journal 'Partecipazione e conflitto'. Email: paola.rivetti@dcu.ie

Comments

Post a Comment