Rape, colonialism and the ongoing after effects of trauma

Review of Adania Shibli (2020) Minor Detail, London: Fitzcaraldo Editions (translated by Elisabeth Jaquette), 112 pp, £12.99

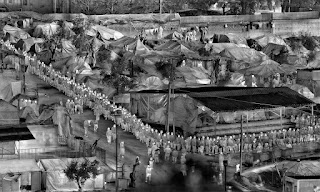

On 12 August 1949 the atmosphere at the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) outpost in Nirim in the Naqab desert near the Gaza Strip was particularly festive. It was the end of an arduous week of dusty chases in the western Naqab sand dunes after Palestinian ‘infiltrators,’ refugees attempting to get back to the homes they had been expelled from by the colonizing Zionist forces. The platoon commander, lieutenant ‘Moshe,’ told his soldiers to get the dining tent ready for a party. Tables were set with sweets and wine and at eight o’clock, he gave his soldiers a pep talk about Zionism and the important contribution they were making to the newly established State of Israel. Towards the end of the party ‘Moshe’ reminded his soldiers of the 12 year old Bedouin girl they had captured earlier that day, now locked up in one of the huts. He gave the men two options: the girl was to be either a kitchen worker or a sex slave. Most of the men shouted ‘we want to fuck,’ so he drew up a three-day gang rape schedule for his three squads. The girl was brought into the outpost, her clothes were ripped off and she was forced into the shower by the platoon sergeant who washed her down with his own hands while the soldiers looked on. She was gang raped by three soldiers. The soldiers then brought in a barber who cut off her long matted hair after which she was forced to shower again in front of the officer and sergeant. During the first night the officer and the sergeant raped her leaving her unconscious. In the morning, as she tried to speak, they executed her and placed her body in a shallow grave.

This was one of the most horrific rape and murder cases in the history of the IDF, ranked the ninth most powerful army globally. The IDF’s ‘most moral army in the world’ self-style description persists despite having waged several wars against Israel’s Arab neighbours since 1948, having periodically assaulted the Gaza enclave, and having operated a brutal racialized regime of occupation in the territories conquered in 1967. The IDF upholds this claim to being a ‘moral army’ to this day, as reiterated by former Chief of Staff Gadi Eisenkot in a letter distributed in April 2016 to all IDF soldiers. Among other things he said: ‘from the day it was founded, the IDF has sanctified important values, among them human dignity and the purity of arms. These values are based on many years of Jewish heritage’.

The Nirim rape and murder case was known about at the time and was recorded in Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion’s 22 August 1949 diary entry (titled ‘It was decided and executed: They washed her, cut her hair, raped her and killed her’). Seventeen of the soldiers involved stood trial for ‘negligence in preventing a crime,’ and some of them served jail sentences. Despite this, the Nirim case was kept secret for a long time and was only publicly exposed when the liberal Israeli daily Haaretz reported the story in 2005, 56 years after it happened.

Most Jewish Israelis refuse to accept that rapes of Palestinian women by Zionist soldiers were frequent occurrences during the 1948 Nakba, despite ample evidence by international agencies including the UN and the Red Cross, and despite historical and archival evidence available through the Israeli state archives (although the archives only covered rape cases in which the rapists were brought to trial). In The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, Israeli historian Ilan Pappe cites a Red Cross official, de Meuron, reporting that ‘as Palestinian men were taken away as prisoners, their women were left at the mercy of the Israelis.’ David Ben-Gurion, Pappe writes, entered news of the rapes in his diary regularly, including one that happened in the northern Palestinian-Israeli city of Acca where ‘soldiers wanted to rape a girl. They killed the father and wounded the mother, and the officers covered for them. At least one soldier raped the girl.’

The Nirim rape is a horrific illustration of the intersection of race and gender in Israel’s permanent war against the Palestinians, and epitomizes what I term Israel’s ‘rape culture.’ The rape of Palestinian women by Israeli soldiers have often been denied. One example is the reaction by the left wing Israeli journalist Uri Avneri, who had served in the pre-state militia which enacted the Nakba, and whose reaction displayed deep-seated anti-Palestinian racism: ‘I knew we committed nearly every human atrocity … everything apart from rape and sex abuse… for racist reasons. Having sex with an Arab woman was considered demeaning.’ Another example is a study by the Israeli sociologist Tal Nitzan who interviewed male Israeli soldiers stationed in Palestinian population centres, and who argues that rather than sexually abusing Palestinian women, the soldiers ‘de-womanized’ them. They described Palestinian women as ‘impossible sexual objects,’ mothers, sexually unattractive and inhuman, or as polluting and impure. Put another way, the soldiers Nitzan interviewed described Palestinian women in racist terms: ‘yuck, she’s disgusting, the very fact that she is Arab means she is disgusting.’

By contrast, Palestinian scholars attest to prevalent rapes of Palestinian women by Israeli soldiers, arguing that during the 1948 Nakba rape was used to terrorize the Palestinian population so as to facilitate the ethnic cleansing of certain areas. Palestinian scholar Isis Nusair interviewed first- and second-generation Palestinian women Nakba survivors who spoke about the violation of honour when describing the fear that accompanied the Nakba. Nusair quoted Nazareth-born Jamileh: ‘When the war broke out, there was fear from what happened in other villages… where they killed and raped.’ Another feminist Palestinian scholar, Nahla Abdo, speaks of ongoing sexual harassment of female Palestinian prisoners in Israeli jails.

All this tallies with the sexualization of Israeli society which is tarnished by a rape culture, which, according to journalist Natasha Roth in an article published in 2016 and asking why so many Israeli women are sexually harassed on a regular basis, is primarily due to its militarized nature. Roth lays the blame for Israel’s rape culture on the occupation: ‘For nearly 50 years, Israelis have lived with the fact that one’s desire for something is worth more than what — or whom — may be harmed in the quest to pursue it. The idea that something is there for the taking simply because one covets it is toxic, contagious, and under Israel’s current leadership, only becoming more entrenched.’

I was thinking of these discussions of the rape of Palestinian women and of Israel’s rape culture when I was reading Adania Shibli’s 2020 novel, Minor Detail. Shibli, a Palestinian writer who divides her time between Jerusalem and Berlin, narrates the rape at Nirim from two totally different viewpoints in an attempt to fathom the reality of what happened to the young Bedouin girl at that IDF outpost. The book is in two parts. The first is told from the view point of the outpost’s commander, un-named in the novel, and the second is told from the view point of a female Palestinian Ramallah-based journalist who comes across the story which overwhelms her due to the ‘minor detail’ of it having happened on her birthday, twenty five years before she was born.

The densely written first part gives readers a glimpse of the mind of the Israeli officer for whom the heat and dust of the southern outpost is so overwhelming that it almost drowns the story of the capture, rape and murder of the young Bedouin girl. Told in the third person – thus distancing the narrative from any reality – there is nothing sexual in the telling, nothing emotional. The officer’s story is but a sequence of events, economically narrated and amounting to an indifferent – and frightening – account of a mindless rape, a mindless, unnecessary murder. Shibli’s style does not allow you to feel for either the girl or the officer – both nameless, both third person cyphers. Perhaps the only character who deserves a degree of our empathy is a lone dog, roaming aimlessly in the desert outpost, yelping and searching water and food. The first part of the novel is ultimately a tale of hollow horror of a banal racializing military act of sexualized murderous abuse.

It is only when you get to the second part of the novel that you become gradually drawn into the reality of the tale. The un-named Ramallah journalist comes across the story and decides to uncover the truth of the Nirim rape case. It is the story of her journey – told in the first person and thus humanizing it so much more than the story of the officer and the dead girl – which she must make in a rented car, using a borrowed credit card, through checkpoints and unfamiliar roads, that makes real the everyday experience of living in occupied Palestine, so near, yet so far from the threatening yet indifferently hovering state of Israel. As she gradually manages to uncover the story of the Nirim rape in a military museum and to follow it in the archive of the neighbouring kibbutz of Nirim, the journalist gets closer to the truth she is seeking, albeit without actually reaching it.

Shibli’s writing brings to life the liminal existence of this Palestinian journalist, anxious, uncertain, terrified yet determined, marginalized yet fully present. It is through her stubborn search for the ‘minor detail’ that was that abhorrent rape that we come face to face with the colonization of Palestine and its intersection with race, gender and sexuality. It is the journalist present-day relentless tale that gets us closer to believing that the rape of Palestinian women by Israeli soldiers was and still is a regular occurrence despite all the racist denials.

The book ends with the journalist circling round the desert army outpost where the rape had taken place. The dog, or rather a dog, is still there, barking and running between the corrugated zinc panels, huts and brick walls of the outposts. Gradually the journalist gets closer and closer to the truth and this makes it difficult for her to leave the area: ‘I wonder whether I'd really seen the girl, or if I’d only imagined her’ (107). She keeps driving around the outpost as the desert shadows begin to appear and she spots an old woman standing on the side of the road. She stop and gives her a lift: ‘She’s probably in her seventies. The girl would have been around the same age now… if she hadn’t been killed. Maybe this old woman has heard about the incident…’ (109). But the journalist does not ask her, and the silence between them stretches on, until the old woman suddenly asks her to stop, and gets out of the car. But ‘before she does, she looks directly into my eyes’ and then continues to talk away until she vanishes into the sandy hills. And the journalist knows that it was the old woman, not the archives or the military museums, who could help her uncover the incident as experienced by the girl, an experience she would now never know the whole truth about.

As you read it, you know that it did happen, that it was just one rape of a Palestinian woman by Israeli soldiers out of many – part of the Zionist colonization, part of Israel’s rape culture. And you sense the palpable after effects of the trauma of the Palestinian past, as lived on in present tense. Because ultimately, there is no factual truth, just the long shadows of the desert, just the whole truth of the experience of the colonized, of the occupation of Palestine.

The book ends as it began, heat, dust, boredom and murderous racist contempt as the journalist runs into a group of Israeli soldiers who raise their guns in her direction: ‘And suddenly, something like a sharp flame pierces my hand, then my chest, followed by the distant sound of gunshots’ (112).

Professor Ronit Lentin's latest publications are Traces of Racial Exception: Racializing Israeli Settler Colonialism (Bloomsbury Academic, 2018) and Enforcing Silence: Academic Freedom, Palestine and The Criticism of Israel (co-edited with David Landy and Conor McCarthy, Zed Books/Bloomsbury, 2020). You read more about professor Lentin's work on her blog, https://ronitlentin.net

Comments

Post a Comment