Intervention and (in)visibility: A comparative analysis of the Western Sahara conflict and Rojava revolution

By Trent Tetterton

Traditional scholarship has forced the trajectories of subnational movements such as uprisings, revolutions, and secessions into a reductive framework of understanding defined by “success” or “failure.” In the case of secession—a term functionally conceptualized as “an attempt by an ethnic group claiming a homeland to withdraw its territory from the authority of a larger state” and applied to movements both to create new states or increase regional autonomy (Horowitz 2011: 158-159) —, “success” has been considered the realization of a secessionist group’s aim. Such an outcome, scholars contend, has historically rested on effective external assistance and international recognition (Horowitz 2011: 159; Dugard and Raič 2006: 99; Fabry 2011: 251).

Yet, despite the arguable need to understand what leads to/detracts from “success,” in the traditional sense, some have challenged this focus. Schwedler, for example, argues that centering on success as state-level metamorphosis obscures “other processes, dynamics, and explanations that link or distinguish […] uprisings across both time and space” (2019). While she speaks primarily to the role that protests have played within uprisings across the modern Middle East, her thoughts may hold relevance for considering the results of external involvement within regional secessionist movements. Rather, perhaps an extended evaluation is required. Aside from impacting a success/failure binary, how else has international involvement affected these mobilizations? What has our focus on success obscured?

I argue here that foreign intervention does not simply articulate success or failure for secessionist movements but rather a range of results, including their (in)visibilization within international politics and discourse. Through a comparative study of the Western Sahara conflict and the Rojava revolution in particular, I show that external influence has respectively produced the invisibility and hyper-visibility of these movements. Namely, while the geostrategic interests of UN actors such as the United States continue to deny the Sahrawis a triumph which international law should afford them, in supporting the Rojava revolution, the same actors have centered the case within the political imaginary of the international Left. Despite its current abeyance, it continues to see widespread support today.

1. Identifying Secessions

Once known as the Spanish Sahara, Western Sahara’s tensions largely originate in 1963 when Morocco lobbied for the UN to recognize it as a non-self-governing territory and requested Spain’s decolonization (Fabry 2011: 257; Hasnaoui 2020: 107). Although UN resolutions require colonial powers to withdraw from these territories and for third parties to coordinate new statehood when decolonized people request it via referendum, at the time, the monarchy reasonably assumed the Sahrawis would seek a formal unification (Hasnaoui 2020: 111).

In 1973, however, they organized around the Polisario Front, and in 1974 announced their desire for full independence, establishing the Algerian-backed Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). Although Spain withdrew in 1975, it divided Western Sahara between Morocco and Mauritania and violent conflict resultantly ravaged the region until the 1991 UN-mediated ceasefire (Hasnaoui 2020: 108-109). A referendum has yet to take place. While some scholars see the conflict as “botched” decolonization rather than secession, Morocco still views the potential loss of Western Sahara as an existential threat and the UN itself regards the conflict as “anti-colonial secession” (Mundy 2017: 62; Mundy 2019; Coggins 2011: 30)

Colonialism likewise marks the genesis of the Rojava revolution. After World War I, the Kurdish people were fragmented into Iraq, Iran, Syria, and Turkey (Gunes 2020: 323). While the Kurds—ideologically led by Abdullah Öcalan in Turkey—for many years sought a “Greater Kurdistan,” in 2004 their ideology pivoted toward Democratic Confederalism, or “democracy without a state,” defined by libertarian municipalism, social ecology, and the deconstruction of all hierarchy (Miley 2020; Dinc 2020: 48). In the context of the Syrian civil war, a Kurdish majority force in north and east Syria put Öcalan’s musings into practice, declaring regional autonomy in 2012.

Considering Rojava’s desire for stateless democracy, it may be argued that the case is inherently not a secession. Yet, many challenge the extent to which Rojava has transcended the nation-state model in practice, and residents often understand the revolution to be both nationalist and separatist in spirit, regardless (Dinc 2020; Galvan-Alvarez 2020; Miley 2020). Moreover, considering Horowitz’s allowance for secession as a demand for increased regional autonomy, the Rojava revolution can be located as secessionist in both form and function.

2. Western Sahara’s Invisibility

|

| In Western Sahara, a man waves the SADR flag in support of Sahrawi independence. Source: wiki commons. |

While international support might include mediation, peacekeeping, military assistance, or the full-scale use of armed force, inter alia (Fabry 2011: 251), the following section considers the effects of UN mediation within Western Sahara’s extant political imbroglio. As will be shown, the Sahrawi independence movement has been staunched by the prevailing geostrategic interests of powerful UN Security Council (UNSC) members which have rendered the conflict “invisible”—specifically, the United States and France’s interests in containing Islamic fundamentalism and economic gain (Solana 2021; Mundy 2017: 53).

2.1 The Failure of UN Mediation

Following the 1991 UN-mediated ceasefire, three periods evidence that the actions of the UN and its Council constituents have both protracted and concealed the Western Sahara conflict. First, after the 1988 UN Settlement Proposals—which reiterated the need for a referendum—were accepted by the parties and seconded by the UN Security General (UNSG) in 1990, the UN established the Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO) in 1991 (Hasnaoui 2020: 113-114). While in implementing MINURSO, UNSG Perez de Cuéllar ostensibly secured a plan for Western Sahara’s decolonization, evaluations now reveal that he had no true intention of holding a vote at all—indeed, the mere threat of one was meant to force Morocco into concessions (Mundy 2017: 64). On this basis, the UN’s principal interest was arguably not to advance a workable solution but rather achieve a quick return to peace, unfortunately at the expense of Sahrawi interests.

Second, as the voter identification process progressed, Morocco became increasingly concerned that the referendum would not work in its favor. As a result, Rabat proposed its first Autonomy Plan in 2000, a plan which UN Special Envoy James Baker promptly found unworkable. In 2003, he in turn proposed the “Peace Plan for the Self-determination of the People of Western Sahara,” defined by a four-year autonomy period and a subsequent referendum offering integration, independence, or autonomy (Theofilopoulou 2017: 44). Although the UNSC initially provided unanimous support and the Polisario Front accepted, Morocco rejected it given the option for Sahrawi independence. France and the United States pursuantly encouraged the remaining council members to retract their support—ignoring Baker’s maintenance of the irreconcilable positions of both sides, they continued to hope for a mutually acceptable proposal (ibid.).

Third, after the UN’s reversion, both Morocco and the Polisario Front submitted new proposals in 2007—Morocco’s providing for autonomy and the Front’s demanding a referendum for potential independence. With Resolution 1754, the Council accepted Morocco’s plan as credible (Theofilopoulou 2017: 47). However, WikiLeaks later revealed that key Council members, including the United States and France, found Morocco’s plan to be almost identical to its Autonomy Plan of 2000—the very plan Baker considered insufficient (ibid.). Regardless, and faced with Morocco’s unyielding insistence, the Council supported the plan even with its shortcomings. Resolution 1754 has been the basis of the UN’s work ever since, and despite periodic negotiations and the efforts of three envoys since Baker, the conflict saw little change until the reignition of armed conflict in November 2020 (ibid.; Drury 2020).

2.2 Western Interests and their Survival

Given the continued failure of UN mediation, it is worth asking: why have UN actors apparently shadowed the conflict by design? Two key reasons prevail. Principally, since the post-Cold War era shift in Western foreign policy from containing Communism to countering Islamic fundamentalism, amicable relations with Rabat have become essential for the advancement of Western geostrategic interests in the region (Solana 2021; Mundy 2017: 68; Mundy 2019). Today, the United States and France see Morocco as absolutely critical for effective counterterrorism in North Africa—a development exacerbated by Morocco’s efforts to present itself as peaceful and the Polisario Front as a terrorist organization (Mundy 2017: 66; Theofilopoulou 2020: 48). And second, access to the kingdom offers significant economic reward given that Western corporate ventures routinely and illegally extract natural resources from the region, including phosphates, fish, agricultural produce, sand, and oil (Solana 2021)

Today, the hegemony of Western interests persists. Former US President Donald Trump’s tweets in December 2020, for example, which proclaimed his recognition of King Mohammed VI’s sovereignty over Western Sahara in exchange for the monarch’s own recognition of Israel, have once more downplayed the legal rights of the Sahrawi people to self-determination (Solana 2021). Even the historic return to violence in November 2020 at the Guerguerat buffer-zone has received scant attention by the media (ibid.). Neither the UNSC nor the Biden administration have taken a stance on the collapse of the 29-year ceasefire, and the new American President retains a challenging policy question: reverse his predecessor’s erratic proclamation and defer to international law, or maintain it to privilege American interests (Fabiani 2021; El Aallaoui 2021; Al Jazeera 2021)? Regardless of its future, the Western Sahara conflict effectively supports that international involvement—in this case, suboptimal mediation efforts—can and has left secessionist movements invisible and forgotten.

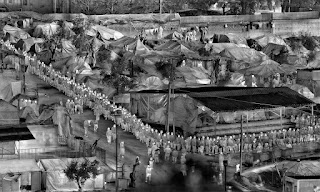

3. The Hyper-Visibility of the Rojava Revolution

|

| Armed female fighters stand beside a YPJ flag during the Rojava revolution. Source: wiki commons. |

In contrast to the Western Sahara conflict, the involvement of external actors has resulted in the hyper-visibility of the Rojava revolution. Within Rojava’s secession, external military support and international attention, primarily from the United States during the fight against the Islamic State (ISIS), initially legitimized the movement, positioning the region as an independent agent from the Assad regime and bolstering its people’s demand for autonomy. While the end of US support provided space for Turkish infiltration, Rojava’s radical democratic experiment remains visible today, inviting continued attention from the international Left (Radpey 2020).

3.1 Rojava’s Utility and American Abandonment

When Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s regime retreated from northeastern Syria in 2012 to attend to military engagements in the southern city of Aleppo, Syrian Kurds were presented with a unique opportunity to implement Öcalan’s philosophies (Miley 2020; Federici 2015: 283). Revolutionary forces, led by the Democratic Union Party (PYD), seized control of the region and established a de facto autonomous region of three cantons: Afrin, Kobane, and Jazira (Holmes 2020). The PYD distinctively established direct democratic citizen’s assemblies and eventually evolved its People’s Protection Units (YPG) and Women’s Protection Units (YPJ) into the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a multi-ethnic force comprised of not only Kurds but Arabs, Assyrians, Armenians, Yezidis, Circassians, and Turkmen (Holmes 2020). Although the PYD efficiently implemented a governance structure which administers justice, preserves law and order, and maintains local institutions, their legitimacy was only enhanced within the regional contest against ISIS (Federici 2015: 83).

The United States, for example, considered coordination with the YPG-J/SDF as crucial for the defeat of ISIS, and in October 2015 it began airdropping weapons and ammunition to the YPG directly and to rely on YPG intelligence (Federici 2015: 85). Its recognition of Rojava as an independent actor, and its subsequent military partnership, initially served to cement the legitimacy of its Öcalan-inspired democratic project. Rojavan revolutionaries, then presented as a key Western ally with substantial regional influence, found themselves both supported and publicized (ibid.).

Yet, after the US-SDF defeat of ISIS in 2017, the alliance crumbled, and the Rojava project has since then suffered a number of misfortunes (Miley 2020). First, when Turkey invaded Afrin in 2018, the United States failed to provision any form of military support (Galvan-Alvarez 2020: 189). Second, in late 2019, former President Trump announced that the United States would withdraw its troops and air cover from northeast Syria, enabling a second Turkish invasion which displaced hundreds of thousands and signaled the end of Rojava’s full autonomy (Miley 2020). While the Assad regime, Turkey, and Russia have also considerably influenced the current state of Rojava, US intervention is a predominant example of foreign involvement which has elevated and visibilized the movement.

3.2 The Gaze of the International Left

Yet, even these setbacks, which again originate from a hegemonic Western interest in curbing Islamic extremism, have not stifled Rojava’s international presence. In a world increasingly marred by violence, tyranny, and unprecedented threats from right-wing nationalism and climate degradation, the Rojava experiment—and its promise of social ecology, gender emancipation, multicultural inclusivity, and stateless direct democracy—has galvanized the likes of anarchists and libertarian socialists, who have witnessed their own political sentiments manifest within the movement (Miley 2020). Images of revolutionary, and often female, fighters engaged in a struggle against hierarchy have led to visits by left-wing politicians, Western academics, and social movement activists, each seeking to learn from the Rojava model (ibid.). And, while Rojava itself exists outside the West, it has found solidarity within and beyond the Kurdish diaspora. RiseUp4Rojava protests, for example, have now taken place in over 30 countries (ibid.; New Internationalist 2020).

Although the PYD has regressed in its achievement of regional autonomy, largely at the hands of fickle foreign actors, it has nonetheless encouraged a shift within the international political imaginary. Despite its current abeyance, the Rojava revolution has forced the Left, and the world as a whole, to envision democracy, statehood, and hierarchy differently. Unlike the Western Sahara conflict, international involvement has thus resulted in Rojava’s hyper-visibility.

4. Conclusion

As the preceding case studies have exposed, outside of securing success or failure, international involvement can also produce (in)visibilization for a given secessionist movement. Western Saharan Sahrawis have yet to be granted a referendum due to the seemingly intentional ineffectiveness of UN mediation, leaving their condition veiled within both politics and the media. Meanwhile, American support for Rojava during the fight against ISIS has catapulted the revolution within the gaze of the international Left and elevated Öcalan’s conceptualization of stateless democracy. While external influence may contribute to success/failure as well as (in)visibilization, these outcomes should not be conflated, even while acknowledging their potential relations. To better understand these and other results, future research might quantitatively and/or discursively explore the differences in each movement’s coverage by international media or investigate the contemporary ideological appeal in Democratic Confederalism. While the future of both secessions remains unclear, they each confirm the need for the international community to defer to international law, support the UN-defined right to self-determination, and commit to higher quality mediation and peacekeeping efforts.

Bibliography

Al Jazeera (2021) ‘Western Sahara: what’s at stake for Joe Biden?’, Al Jazeera, 11 January. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/1/11/western-sahara-whats-at-stake-for-joe-biden (Accessed 14 May 2021).

Coggins, B. (2011) ‘The history of secession: an overview’, in Pavković, A. and Radan, P. (eds.) The Ashgate research companion to secession. New York: Routledge, pp. 23-43. doi: 10.4324/9781315613543.

Dinc, P. (2020) ‘The Kurdish movement and the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria: an alternative to the (nation-)state model?’, Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern studies, 22(1), pp. 47-67. doi: 10.1080/19448953.2020.1715669.

Drury, M. (2020) ‘Sahrawi self-determination, Trump’s tweet and the politics of recognition in Western Sahara’, Middle Eastern Report Online, n.p. Available at: https://merip.org/2020/12/sahrawi-self-determination-trumps-tweet-and-the-politics-of-recognition-in-western-sahara/ (Accessed 14 May 2021).

Dugard, J. and Raič, D. (2006) ‘The role of recognition in the law and practice of secession’, in M.G. Kohen (ed.) Secession: international law perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 94–137.

El Aallaoui, A. (2021) ‘How Biden can undo Trump’s dirty deal with Morocco and Israel over Western Sahara’, Haaretz, 21 February. Available at: https://www.haaretz.com/middle-east-news/.premium-how-biden-can-undo-trump-s-dirty-deal-with-morocco-and-israel-over-western-sahara-1.9549422 (Accessed 14 May 2021).

Fabiani, R. (2021) ‘Why the U.S. should reengage in Western Sahara’, World Politics Review, 17 March. Available at: https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/articles/29499/why-the-u-s-should-reengage-in-the-western-sahara-conflict (Accessed 18 May 2021).

Fabry, M. (2011) ‘International involvement in secession conflict: from the 16th century to the present’ in Cordell, K. and Wolff, S. (eds.) Routledge handbook of ethnic conflict. New York: Routledge, pp. 251-266.

Federici, V. (2015) The rise of Rojava: Kurdish autonomy in the Syrian conflict. SAIS Review of International Affairs, 35(2), pp.81-90.

Galvan-Alvarez, E. (2020) ‘Rojava: a state subverted or reinvented?’, Postcolonial Studies, 23(2), pp. 182-196, doi: 10.1080/13688790.2020.1751910.

Gunes, C. (2020) ‘Approaches to Kurdish Autonomy in the Middle East’, Nationalities Papers, 48(2), pp. 323–338. doi: 10.1017/nps.2019.21.

Hasnaoui, Y. (2020) ‘The United Nations leadership role in solving the Western Sahara conflict: progress or delays for peace?’, Journal of Liberty and International Affairs, 4(3), pp. 106-121.

Holmes, A. (2020) ‘Arabs across Syria join the Kurdish-led Syrian democratic forces’, Middle Eastern Report, 295, n.p. Available at: https://merip.org/2020/08/arabs-across-syria-join-the-kurdish-led-syrian-democratic-forces-295/ (Accessed 14 May 2021).

Horowitz, D. (2011) ‘Irredentas and secessions: adjacent phenomena, neglected connections’, in Cordell, K. and Wolff, S. (eds.) Routledge handbook of ethnic conflict. New York: Routledge, pp. 158-168.

New Internationalist (2020) ‘Defending Rojava’, New Internationalist, 10 September. Available at: https://newint.org/features/2020/09/10/defending-rojava (Accessed 14 May 2021).

Miley, T. (2020) ‘The Kurdish freedom movement, Rojava and the Left’, Middle East Report Online, n.p. Available at: https://merip.org/2020/07/the-kurdish-freedom-movement-rojava-and-the-left/ (Accessed 14 May 2021).

Mundy, J. (2017) ‘The geopolitical functions of the Western Sahara conflict: US hegemony, Moroccan stability and Sahrawi strategies of resistance’, in Ojeda-Garcia, R., Fernández-Molina, I. and Veguilla, V. (eds.) Global, regional and local dimensions of Western Sahara’s protracted decolonization. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 53-78.

Radpey, L. (2020) Assessing international law on self-determination and extraterritorial use of force in Rojava. Available at: https://www.lawfareblog.com/assessing-international-law-self-determination-and-extraterritorial-use-force-rojava (Accessed 14 May 2021).

Schwedler, J. (2019) ‘Thinking Critically About Regional Uprisings’, Middle East Report, 292(3), n.p. Available at: https://merip.org/2019/12/thinking-critically-about-regional-uprisings/ (Accessed 14 May 2021).

Solana, V. (2021) ‘An invisible war in Western Sahara’, Middle East Report, 298, n.p. Available at: https://merip.org/2021/04/an-invisible-war-in-western-sahara/ (Accessed 14 May 2021).

Theofilopoulou, A. (2017) ‘The United Nations’ change in approach to resolving the Western Sahara conflict since the turn of the twenty-first century’, in Ojeda-Garcia, R., Irene Fernández-Molina, I. and Veguilla, V. (eds.) Global, Regional and Local Dimensions of Western Sahara’s Protracted Decolonization: When a Conflict Gets Old (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), p. 37-51.

About the author

Trent Tetterton is an Erasmus Mundus scholar currently completing the International Master in Security, Intelligence, and Strategic Studies offered jointly by the University of Glasgow, Dublin City University, and Charles University. In May 2020, he graduated with distinction from the United States Naval Academy with a BSc in Aerospace (Astronautical) Engineering and was commissioned as a nuclear submarine officer in the United States Navy. He is the Senior Editor for the University of Glasgow based think tank The Security Distillery, and his current research interests include the intersection between identity politics and regional security.

Comments

Post a Comment