Suicide bombing as a method of political violence in the MENA region: A new research perspective

|

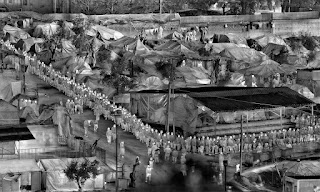

| An Afghan police officer receives treatment for wounds sustained in a suicide bombing. Source: Wiki commons. |

Introduction

The prevalence of suicide Improvised Explosive Device (IED) attacks in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) has drawn significant attention from academia. Although over the past 10 years the number of suicide bombings have proliferated, becoming a consistent feature of intra-state conflicts (AOAV, 2019), existing approaches to understanding political violence in the MENA region have not done enough to offer meaningful and non-Orientalist analysis. As a result, this piece argues that there is a pressing need to move in a new direction.

In the aftermath of 9/11 and the ensuing ‘War on Terror,’ academia became focused on the psychology of suicide bombers (Ward, 2018: 88), often concluding that this form of political violence is driven by cultural or religious factors indigenous to the MENA region. This overwhelming focus on individual psychology has created an understanding of the phenomenon of suicide bombing that is highly flawed, and Orientalist. An evolutionary and context-specific approach to the nature of suicide bombing at the organisational level in the MENA region can explain the phenomenon more effectively than research which paints it as a uniquely Islamic or ‘Arab’ problem.

First, this piece critically analyses the Orientalist approaches present in much of the scholarship on suicide bombings. Second, the new framework drawn from Hafez (2006), Revill (2016), Overton (2019), and Veilleux-Lepage (2020) will be set out to create conditions for researching the phenomenon in a way that moves away from Orientalist scholarship. Third, this new framework will be applied to the organisational and supporting constituency level of Hamas, The Palestinian Islamic Jihad, ISIS, and Al-Qaeda to reframe the suicide bomber as a result of the logical evolution of political violence in the context of asymmetric conflicts. While political violence might be dressed in the language of religion and culture, it is the product of existing political grievances, decreases in political opportunity, and specific conflicts (Aggarwal, 2011; Dyrstad and Hillesund, 2020).

Orientalism and the existing scholarship

Focusing on the psychology of the suicide bomber, scholars of international politics, terrorism, and security have often failed to recognise that, while aspiring toward an objective universalism, their research was embedded within a particular socio-political moment (Aggarwal, 2011: 4). That moment was the ‘War on Terror’ which drove Orientalist and essentialist perceptions of violent individuals and organisations in the MENA region. As Horgan (2014) and Silke (1998) have highlighted, part of the scholarship was seriously biased, with scholars labelling individuals terrorists before research begins and making moral and normative judgements about them. On a similar note, Jackson (2007) has examined over 300 academic papers through discourse analysis, concluding that the political and academic discourses of ‘Islamic terrorism’ are unhelpful because they are highly politicised, intellectually contestable, damaging to community relations, and practically counter-productive (Jackson, 2007: 394).

As mentioned, much of the existing scholarship focuses on the psychology of the suicide bomber. One example is Merari et al. (2009) who applied clinical tests to a group of ‘failed’ suicide bombers from Palestine, who were captured or whose devices failed to detonate. While Elster (2005: 257) highlighted that this group presents specific characteristics due to their survival bias, the ‘successful’ suicide bombers not being accounted for in the resulting research, which should be duly considered. The focus on psychology deploys a vocabulary of instincts and motivations to define Muslims - and in turn the Western Self as its cultural opposite. Just as Said (1978) warned, the West has an authoritative position in producing the Orient politically, sociologically, and ideologically, this production continues in scientific work. The scholarship on the suicide bomber, viewed as the embodiment of the opposition to normative Western values, provides ample sets of research fraught with flaws and Orientalist prescriptions of psychology to both individuals and organisations. Studies such as Merari et al. (2009) are not alone. In a comprehensive review of the psychological literature on suicide bombing, Aggarwal (2011) observed that researchers often locate the psychology of suicide bombers in the culture of their host societies. A clear example of this can be seen in Falk’s study:

The personality traits of the Arabs discussed by Hamid Ammar and Sadiq Jalal al-Azm are those of a narcissistic child who is unable or unwilling to face the difficulties of its life, internal and external. The child unconsciously falls back on emotionally regressive defences such as denial, projection, and externalisation, being dishonest with both itself and the outside world. The effects of such character structure on the Arab-Israeli conflict are disastrous. (Falk, 2004: 157)

The essentialist interpretation of the ‘traits of the Arabs’ is clear here as Falk falls back on Orientalist tropes of irrationality and a maternal relationship between the rational West and an emotional Orient. Aggarwal (2011) highlights how common similar explanations for conflicts in the MENA region are. The supposed “irrationality” of the “Arab psychology” is directly exported into explanations of suicide bombing. This form of violence has been presented as indigenous to Islam, Arabs, and the geographical boundaries of the MENA region. The incorporation of these problematic assumptions into most approaches displays the need for a new framework.

Further, Lachkar proceeds to criticise ‘‘Islamic child-rearing”, which ‘‘attempts to repudiate all aspects of dependency and perceived all personal desires, needs, and wishes as tantamount to weakness and failure, hence the link to borderline personalities” (2002: 17). Similarly, Aggarwal (2011) picks up on Lester et al. (2004), who also discuss “Islamic child-rearing”. As they imply, childhood in the MENA region leads to suicide bombing:

Suicide bombers are typically raised in very strict fundamentalist Islamic sects whose teachings they accept. They do not come to their belief systems by a rational appraisal of alternative ideologies as adults. They accept the ideology in which they are raised. (Lester et al., 2004: 291)

Here, Islam as a religion, culture and education system is seen to motivate militants toward violence. No first-order analysis of sects or religious teachings is offered, let alone a more sophisticated, second-order analysis of how some might dress political and social messages within the cloth of religion to pursue political agendas (Aggarwal, 2011: 13). The scholarship surveyed does not scratch the surface of the rather superficial central suggestion that frames the suicide bomber as a specific and irrational product of Islam.

Of course, such a suggestion does not stand up to interrogation. Anarchist movements deployed the first recorded suicide bombing with Ignaty Grinevitsky’s assassination of the Russian Tzar in 1881 (Radzinskiĭ, 2005: 374), not to mention the widely known Japanese ‘Kamikaze’ (Overton, 2019). A cost-effective, tactically flexible and highly visible form of violence, the suicide bomber has gained popularity, from the Palestinian Liberation Organisation and Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia to the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (Overton, 2019). The approaches outlined above fail to explain the prevalence of suicide bombing in other contexts than the MENA or Islam-dominated ones, as well as failing to account for a variety of motivations for political violence within the MENA region, other than Islam. Nonetheless, there has been a high prevalence of suicide bombing in the MENA region and the reasons for this need to be explored.

A New Direction

As outlined above, the focus on the psychology of the suicide bomber has often led to Orientalist generalisations about culture, politics, individuals and communities. The evolutionary framework proposed by Yannick Veilleux-Lepage (2020) suggests an alternative path. Drawing on evolutionary theory, we can explain how groups and individuals expand their methods of contention through an iterative process of trial and error. Asymmetric conflicts have been a crucial factor in the proliferation and normative acceptance of Improvised Explosive Devices as a popular method of violence in the MENA region, meaning that specific milieus have fuelled the emergence of suicide bombing as a paradigmatic weapon of asymmetric conflict (Revill, 2016: 60).

Hafez (2006) focuses on individual motivations, organisational strategies, and societal conflicts in his framework for understanding the conditions leading individuals to engaging in suicide bombing (2006: 165), and the work of Kalyvas and Sánchez-Cuenca (2005) examines the perceptions of violence and the role of supporting constituencies to explain the ideological and social framings of this type of violence. This is vital because many terror groups see themselves as representing the communities they are embedded in and rely on them for support (Bloom and Horgan, 2008: 579). The framing of suicide bombings as an acceptable violence is therefore a strategic and rational political act such groups engage in. Alongside this, Dyrstad and Hillesund (2020) argue that support for political violence is prevalent when communities experience the combination of the existence of grievances and the perception of decreased political opportunities. This combination creates the conditions for the acceptance of violence within a supporting constituency when dressed in familiar social and cultural images.

The combination of these approaches allows a more holistic view of the conditions that lead to the proliferation and resilience of suicide bombing as a method of political violence in the MENA region. Crucially this framework explains the prevalence of suicide bombing in the MENA region without relying on the analysis of the phenomenon as something indigenous, psychological, or specifically Islamic. These outdated ideas have often led to problematic assumptions about the origins of violence in the MENA region damaging the quality of research.

Hamas and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad

It is important that the factors that prompt organisations to use suicide attacks are disaggregated from regional generalisations. A focus on Hamas and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ), the two organisations which initiated the use of suicide bombing in Palestine and account for the most lethal attacks is necessary (Benmelech and Berrebi, 2007: 230). In this case developmental and functional explanations can be applied. In 1992 the Israeli government under Yitzhak Rabin deported 415 leaders of the first intifada, including members of Hamas, the PIJ, and other activists to a remote part of southern Lebanon (Overton, 2019). During this time there was direct contact with Hezbollah that increased the propensity for suicide attacks and the targeting of civilians (Ricolfi, 2004: 91). The exiles learned how to create sophisticated explosive devices, studied counter insurgency methods, and were taught how to carry out suicide attacks (Overton, 2019). In the year that followed, many of the exiled returned to Palestine, and Hamas and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad perpetrated eight suicide attacks in Israel in 1993, asserting themselves as leading forces in the Palestinian struggle (ibid.). Between 1993 and 1997, suicide bombings by various actors in Palestine killed 175 people (including 21 suicide bombers) and had wounded 928 others (Brym and Araj, 2006: 1969). A later devastating wave of suicide bombings began in 2000 with the second intifada. By July 12, 2005, suicide bombing accounted for the deaths of an additional 657 people (including 148 suicide bombers) and had wounded 3,682 others (ibid.). Hamas, the PIJ and the Fatah affiliated al-Aqsa Martyrs' Brigades accounted for the vast majority of and the most lethal of these attacks (Benmelech and Berrebi, 2007: 230). Functionally, this innovation was a logical step to penetrate the extensive security apparatus of Israel to target civilians (Horowitz, 2015: 72). These organisations gained legitimacy and support in the nationalist struggle by demonstrating their capability to attack Israel through this innovation of violence (Bloom, 2004). Secular groups later adopted the tactic. This case suggests that Hamas and the PIJ initially deployed the suicide bomber as a tactical development to breach the extensive security of Israel. It was a technique that thrived in the cyclical violence of asymmetric conflict. For instance, the Israeli Security forces killed 319 Palestinians during rioting at the start of the second intifada (Brym and Araj, 2008: 492). In response there was a wave of suicide bombings (Araj, 2008:286). Crucially the use of suicide bombing has increased and decreased significantly as the context of the conflict evolved. In 2004 after the death of Yasser Arafat and the adoption of a non-aggressive stance by Fatah, Hamas stopped deploying suicide bombers. The PIJ continued to launch suicide attacks in the following months yet electoral support for Hamas grew, and in the January 2006 elections Hamas secured 74 out of 132 seats (Brym and Araj, 2008: 498). The growth of popularity for Hamas and the PIJ securing no seats suggests a shift in opinion towards suicide bombings in Palestine (ibid.). Although there is a multitude of factors to this shift, it displays that suicide bombing is not an inherent feature of Palestinian culture or psychology. It is a technique that evolved and came to be favoured and then abandoned in specific contexts.

Al-Qaeda in Iraq and ISIS

If we take the example of Al-Qaeda in Iraq and the elements which would become ISIS, the evolutionary and context-specific approach can explain the path that brought them to widespread use of suicide bombing. In terms of the developmental evolution of violence, a successful precedent had been set by the suicide bombing which led to the expulsion of US forces from Lebanon in 1984 (Overton, 2019). In Iraq’s internment facility at camp Bucca, managed by the U.S. military, a process of information-sharing took place for over a decade with inmates creating networks and sharing strategies (Chulov, 2014). Revill (2016) highlights that the conditions in Iraq provided numerous opportunities for suicide bombings. First, extensive explosives and IED precursor materials were acquired by the pilfering of the former regime’s caches of military hardware. Second, there was expertise for IED development, with the demobilisation of Baathist regime forces but also due to the growing availability of information on the Internet. Third, opportunities for attacks were generated by the availability of targets, both in the form of coalition troops engaged in population-centric security measures and institutions of the embryonic Shia-dominated state. Fourth, the long-term influence of ideology which was interpreted by some as justifying the killing of apostates (Revill, 2016: 60). This demonstrates the specific conditions of suicide bombing proliferation in Iraq, which cannot be applied to the entire MENA region.

One possible explanation for the resilience of this form of violence is that it provides an economy of means, propaganda of the deed, and a constant evolution of its tactical use for actors. ISIS’s desire to craft a caliphate has much of its roots in a particular ideology, but its employment of violence is wrapped in the social messages of this ideology; it is not a product of it. ISIS went on to deploy the Suicide Vehicle Borne Improvised Explosive Device (SVBIED) as a crucial component of their violence (Kaaman, 2019: 16). They crafted various evolutions of the SVBIED in factory-like production, including versions with armour and protections for driver and explosive (ibid.). This has its genesis in the type of war that ISIS was fighting: an asymmetric conflict in which the SVBIED played a crucial role by punching holes in enemy positions to allow ISIS fighters to take advantage of weak points in the formation of superior military forces (ibid.). Furthermore, this sort of violence has spread in many ways from secular to religious groups, from Shia to Sunni, from nationalists to separatists. The multi-dimensional nature of the evolution of suicide bombing in the region contradicts Orientalist understandings of the violence as grounded in anything indigenous or Islamic.

Conclusion

Ultimately, moving away from viewing psychology, ideology, or religion as the origin of suicide bombing enables us to explain the evolution of this form of violence in the MENA region without prescribing Orientalist generalisations. These factors are still important and contribute to the conditions for engaging in this form of violence. However, viewing these factors as the social messages that various forms of violence are dressed in rather than the root cause is a step in the right direction. The framework suggested by Veilleux-Lepage (2020) provides an important basis for evolutionary and context-specific explanations for the proliferation of different forms of violence. In combination with the work of Hafez (2006), Revill (2016), and Overton (2019), we can begin to analyse the phenomenon of the suicide bomber in the context of asymmetric conflicts and the wider conditions necessary for this form of violence to thrive. These conditions are not indigenous to the MENA region. Ideological justifications, secular or religious, are important but cannot be seen as the sole driver of suicide bombing. Further, there are reasons to remain sceptical about the role of moral or ideological preferences. For instance, Hamas committed itself at the start of the 1990s to not kill civilians. When the organisation began killing civilians in 1994 it found plenty of reasons for justifying the shift (Kalyvas and Sánchez-Cuenca, 2005: 215). For instance, in order to justify the logic of targeting civilians, Hamas repeatedly highlighted that there is no comparison between Israeli military might and Palestinian weakness (Hroub, 2000: 248). As well as insisting that targeting civilians was a necessary cost as they represented an Achilles heel of the Israel and that their deaths were a response to Israeli violence (Hroub, 2000: 249). Nonetheless, ideology and religion provide justification for normative shifts, reframe the violence in a way that is more acceptable for supporting constituencies, and seem to motivate some individuals to engage in violence. The cases of Iraq and Palestine have seen this method of violence proliferate due to proximate inspiration and the tactical necessity that asymmetric conflicts provide. Further application of this approach to disaggregated cases of suicide bombing would provide a basis of research for a new direction. A move away from Orientalist understandings of culture and religion in the MENA region and an insistence on disaggregation to reflect the diverse reality of this form of violence may address some of the weakness of previous research.

Bibliography

Aggarwal, N. K. 2011. “Medical Orientalism and the War on Terror: Depictions of Arabs and Muslims in the Psychodynamic Literature post-9/11.” Journal of Muslim Mental Health. Vol. 6. pp. 4-18.

AOAV. 2020. Explosive Violence Monitor: 2019. Available at: https://aoav.org.uk/2020/explosive-violence-in-2019-2/ [Accessed 21 Apr. 2021].

Araj, B. 2008. “Harsh State Repression as a Cause of Suicide Bombing: The Case of the Palestinian–Israeli Conflict.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. Vol. 31. pp. 284-303.

Baruch, E. H. 2004. “Psychoanalysis and Terrorism: The Need for a Global ‘Talking Cure’.” Psychoanalytic Psychology. Vol. 20. pp. 698-700.

Benmelech, E., and Berrebi, C. 2007. “Human Capital and the Productivity of Suicide Bombers.” Journal of Economic Perspectives. Vol. 21. pp. 223-238.

Bloom, M., and J. Horgan. 2008. “Missing Their Mark: The IRA’s Proxy Bomb Campaign.” Social Research. Vol. 75. pp. 579-614.

Bloom, M. 2004. “Palestinian Suicide Bombing: Public Support, Market Share, and Outbidding.” Political Science Quarterly. Vol. 119. pp. 61-88.

Brym, R., and Araj. B. 2006. “Suicide Bombing as Strategy and Interaction: The Case of the Second Intifada” Social Forces. Vol. 84. pp. 1970-1984.

Brym, R., and Araj. B. 2008. “Palestinian Suicide Bombing Revisited: A Critique of the Outbidding Thesis” Political Science Quarterly. Vol. 123. pp. 485-500.

Chulov, M. 2014. “Isis: The Inside Story.” The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/dec/11/-sp-isis-the-inside-story [Accessed 21 Apr. 2021].

De Mause, L. 2002. “The Childhood Origins of Terrorism.” The Journal of Psychohistory. Vol. 29. pp. 340-348.

Dyrstad, K., and S. Hillesund. 2020. “Explaining Support for Political Violence: Grievance and Perceived Opportunity.” Journal of Conflict Resolution. Vol. 64. pp. 1724-1753.

Elster, J. 2005. “Motivations and Beliefs in Suicide Missions.” Making Sense of Suicide Missions, ed. by D. Gambetta. Chapter 7. pp. 233-259.

Falk, A. 2004. “Fratricide in the Holy Land: A Psychoanalytic View of the Arab-Isreali Conflict.” Journal of Interdisciplinary History. Vol. 37. pp. 335–336.

Hafez, M. 2006. “Rationality, Culture, and Structure in the Making of Suicide Bombers: A Preliminary Theoretical Synthesis and Illustrative Case Study.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. Vol. 29. pp. 165-185.

– – –. 2007. Suicide Bombers in Iraq: The Strategy and Ideology of Martyrdom. Barnes and Noble. 1st Edition. pp. 1-312

Horgan, J. 2014. The Psychology of Terrorism. Routledge. 2nd Edition. pp. 1-206.

Horowitz, M. C. 2015. “The Rise and Spread of Suicide Bombing.” Annual Review of Political Science. Vol. 18. pp. 69-84.

Hroub, K. 2000 “Hamas: Political Thought and Practice.” Institute for Palestine Studies. pp. 1-329.

Jackson, R. 2007. “Constructing Enemies: Islamic Terrorism in Political and Academic Discourse.” Government & Opposition. Vol. 42. pp. 394-426.

Kaaman, H. 2019. “Car Bomb as Weapons of War ISIS’s Development of SVBIEDS, 2014–19.” Middle East Institute Policy Paper 2019–7. pp. 1-16.

Kalyvas, S. N., and I. Sánchez-Cuenca. 2005. “Killing Without Dying: The Absence of Suicide Missions.” Making Sense of Suicide Missions, ed. by D. Gambetta. Chapter 6. pp.209-232

Lachkar, J. 2002. The Psychological Make-Up of a Suicide Bomber. Bloomusalem Press. Vol. 29. pp. 349-367.

Lankford, A. 2011. “Could Suicide Terrorists Actually Be Suicidal?” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. Vol. 34. pp. 337-366.

Lester, D., B. Yang, and M. Lindsay. 2004. “Suicide Bombers: Are Psychological Profiles Possible?” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. Vol. 27. pp. 283–295.

McCauley, C. 2014. “How Many Suicide Terrorists are Suicidal?” Behavioral and Brain Sciences. Vol.4. pp.373-374.

Merari, A., I. Diamant, A. Bibi, Y. Broshi, and G. Zakin. 2009. “Personality Characteristics of ‘Self-Martyrs’/’Suicide Bombers’ and Organizers of Suicide Attacks.” Terrorism and Political Violence. Vol.22. pp.87-101.

Mintz, A., and D. Brule. 2009. “Methodological Issues in Studying Suicide Terrorism.” Political Psychology. Vol. 30. pp. 365-371.

Overton, I. 2019. The Price of Paradise. Quercus. pp.1-436.

Palmer, I. 2007. “Terrorism, Suicide Bombing, Fear, and Mental Health.” International Review of Psychiatry. Vol. 19. pp. 298-296.

Radzinskiĭ, E. 2005. Alexander II: The Last Great Tzar. Free Press. p.374.

Revill, J. 2016. Improvised Explosive Devices: The Paradigmatic Weapon of New Wars. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 1-109.

Ricolfi, L. 2005. “Palestinians 1981-2003.” Making sense of suicide missions, ed. by D. Gambetta. Chapter 3. pp. 77-116.

Said, E. W. 1978. Orientalism. Vintage Books. pp. 1-368.

Silke, A. 1998. “Cheshire-cat Logic: The Recurring Theme of Terrorist Abnormality in Psychological Research.” Psychology, Crime & Law. Vol. 4, pp. 51-69.

Silverman, H., and J. Prager. 2004. “The Middle East Crisis: Psychoanalytic Reflections.” International Journal of Psychoanalysis. Vol.85, pp. 1265-1268.

Veilleux-Lepage, Y. 2020. How Terror Evolves: The Emergence and Spread of Terrorist Techniques. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 7-46.

Victoroff, J. 2005. “The Mind of the Terrorist.” Journal of Conflict Resolution. Vol. 49, pp. 3-36.

Ward, V. 2018. “What Do We Know About Suicide Bombing?” Politics and the Life Sciences. Vol. 37, pp. 88-112.

About the author

Comments

Post a Comment