A Gender Analysis of Western Media Narratives of the YPJ War against the IS

|

| Asia Ramazan Antar, who was called "the Kurdish Angelina Jolie” by global media during the war against the Islamis State. Source: Wikimedia Commons By Hoang Thi Kim Quy |

How do the Western media cover Kurdish female warriors

Though Kurdish women have been pushing for political rights since the 1980s, the exposure of Kurdish women in the Western media has grown only since the enhanced visibility of their military capabilities during the Kurdish military campaigns against IS (Dean, 2019).

Feminist standpoint theory, initially articulated and presented by Nancy Hartsock (1983), is founded on the idea that a larger understanding of politics and society is socially shaped by and primarily based on the lives of men from ruling races, classes, and cultures, which are artificially elevated to a universal standard. Acknowledging that the difference between men's and women's lived experiences offer essential tools for feminist work, this theory promotes the use of women's daily lives – as well as the lives of other marginalised groups- as a foundation for knowledge construction and as a critique of dominant knowledge centered on men's lives (Harding, 1991). In addition, not only does feminist standpoint theory aim to accomplish fundamental feminist goals by reflecting on gender inequalities and on achieving emancipation, but it also aims to expose injustice and inspire acts of resistance (Allen, 1996).

Since standpoint feminism allows oppressed people to talk about their lives, it explicitly addresses finding new voices. Women and other oppressed groups can experience consciousness-raising (Smith, 1987) as they share the institutional oppression they face with each other. This can lead to resistance, building on their willingness to share their experiences as oppressed people.

Following this reasoning, women's representation in the media is influenced by gender stereotypes. Feminists worldwide have long acknowledged that the media has a profound and long-lasting impact on how current gender stereotypes are presented (Sharda, 2014). Gender stereotypes are preconceived notions about the characteristics that distinguish men and women (Tartaglia & Rollero, 2015). Women are stereotyped as reliant, frail, inexperienced, emotional, afraid, versatile, passive, modest, soft-spoken, gentle, and as caretakers. Simultaneously, men are stereotyped as powerful, concentrated, intense, and assertive, and as strong, capable, influential, and rational decision-makers (Sharda, 2014). Consequently, men are associated with power and leadership roles, while women are associated with caring and relational roles (Rollero, 2013). These gender stereotypes have also been clearly expressed through women's appearance and portrayal in the media. Furthermore, according to the Fourth Global Media Monitoring Project Report (GMMP 2009-2010), compiled by Macharia et al. (2010), women account for less than a quarter (24%) of people seen, heard, or read about on television and in print news around the world. Thus, the media shares a responsibility for perpetuating gender inequality in our culture (Sharda, 2014).

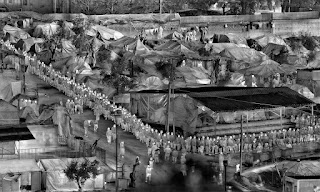

Based on the above feminist analysis, the visibility given to the YPJ female soldiers by the Western media, following their engagement against IS since 2014, deserves special attention. As of 2017, the number of all-female militia personnel was around 24,000 (Perry, 2017). Women's self-defence units, women's schools, courts, cooperatives, and independent women's bodies operate in parallel to other institutions and popular platforms at the same governance level in the three cantons of Rojava (Dean, 2019). This level of activism of women in society led the Western media to increasingly focus on Kurdish women fighters, marking one of the rare times when women were represented as playing an active rather than a passive role in society, particularly during wars. Pictures of female warriors have made it to the front pages of major newspapers and magazines.

An unofficial search on Google in English for the words "Kurdish female soldiers" from March 15, 2011 (the launch of the Syrian conflict) to December 31, 2013, generated 5,230 hits over 33 months. Between January 1, 2014, and May 1, 2015, a 16 months Google search yielded 27,500 results (Tank, 2017). Along with such comprehensive coverage, the Western media created gendered and racialised symbols based on descriptions of Kurdish female fighters, such as 'the blonde angel of Kobane'. According to BBC Trending (2014), the 'Angle of Kobane' is a story about a Kurdish fighter named Rehana, who was photographed at a ceremony for volunteers and was wearing a military uniform. Thousands of viewers shared this picture on Twitter and Facebook, with stories about her bravery and the killing of many IS fighters. The Kurdish blogger Ruwayda Mustafah said to BBC Trending (2014): "She captivated everyone with her pretty eyes and blonde hair. She has a huge fan base. Everyone that I come across admires her because she symbolises what everyone wants to see. That women and men are standing up against barbaric force in the region."

In a Financial Times (FT) report, Solomon (2014) described YPJ fighters as a rare emblem of women's liberation in a conservative society. He quoted a statement of a Kurdish female soldier saying that military might is no longer a man's monopoly, and that the YPJ demonstrates that women can be guardians, too: in fact, they are capable of defending themselves and their country. The presence of female Rojavan soldiers in the Western media did not only mark one of the unusual occasions when women have played active rather than traditional roles, but it also raised the profile of Kurdish women in the public sphere, allowing for a greater understanding of the injustices perpetrated against Kurds in general (Shahvisi, 2018).

Nevertheless, the image of Kurdish female fighters in the global media, particularly the Western media, is significantly affected by gender stereotypes. Western media reports mainly focused on the female guerrillas' motivation for fighting, limiting all the possible reasons to just one, that is overcoming patriarchal repression and escaping their victim status. In many newspaper articles, Kurdish female fighters are portrayed as warriors fighting for women's rights and against the harsh gender inequality prevalent in the Middle East. Tavakolian (2016) quoted Torin Khairegi, an eighteen-year-old fighter, in a Huck Magazine article, saying: "We live in a world where women are dominated by men. We are here to take control of our own future. When I am at the frontline, the thought of all the cruelty and injustice against women enrages me so much that I become extra-powerful in combat." Farashin Mehriva, another female Kurdish fighter, is reported as saying: "We are fighting for the freedom of all women in the world. ISIS and many other anti-women groups want to wipe women off the Earth. But YPJ won't allow that." Reporting for Reuters, Dehghanpisheh & Georgy (2016) quoted Vaysi, a 32-year-old Kurdish fighter, saying: "I saw on television that Daesh is torturing women, and it made my blood boil. I decided to go and fight them."

In these media reports the struggle of the female Kurdish YPJ fighters could only be defined in terms of a gender resistance, and not in terms of more extensive, popular political initiatives. In other pieces of news, many female Kurdish fighters were described as becoming guerrillas because they were victims of conflict and had no choice but to fight. For example, in an article published in The Guardian, Mahmood (2015) told the story of a nineteen-year-old Syrian Kurd, Shireen Taher, who lost her father in a car bomb attack. Her brother noted that the death of Shireen's father jolted her into following his will and becoming a formidable warrior. Another Kurdish woman fighter shared her sense of pride in becoming a soldier. She said that she had two choices: stay in the house and allow time for ISIS to arrive, or enter the YPJ and defend her family, her people, and Rojava (Subramanian, 2020). Hughes (2019) wrote the stories of Kurdish female fighters in The Mirror, including a statement by a 19-year-old woman who gives her name as Kurdistan: "We do not fight because we want to kill people. We do it to protect those we love."

Significantly, Tank (2017) argues that these Kurdish female fighters are mainly identified as members of their families, with personal accounts of poverty and revenge serving as an explanation for their decision to join the Kurdish cause and armed fight. The media's obsession with Kurdish female fighters speaks to a preconceived idea about Kurdish women as passive victims, who are now portrayed in the media as performing exceptional tasks. Through such representations, the Western media perpetuates the stereotype of the underprivileged Kurdish woman who must resort to violence to fight for her rights, in opposition to the modern and civilised Western world, where women's rights are guaranteed by the law and the democratic system. In a sense, the Western media are telling the reader that Western women do not need to engage in a struggle for their rights because they are not oppressed in the same way as these "impoverished women”. In fact, considering what IS has done to the women living in the places it had taken over, it is only natural and understandable that Kurdish women join the armed struggle against IS.

Conclusion

Today's unlimited availability of information does not offer neutral news, on the contrary it may subconsciously reinforce existing inequalities, without the audience realising it (Sharda, 2014). Gender stereotyping is a good example of a prism through which the world's problems are analysed and narrated. The fight of the female Kurdish warriors does not escape this logic. Although the global media's attention, especially in the West, has given Kurdish women many opportunities to express their voice, their representation is still articulated through Orientalist and sexist stereotypes.

Bibliography

Allen, B. J. (1996). Feminist standpoint theory: A black woman’s (re)view of organizational socialization. Communication Studies, 47(4), 257–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510979609368482

BBC Trending. (2014, November 3). #BBCtrending: Who is the “Angel of Kobane”? BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-29853513

Dean, V. (2019). Kurdish Female Fighters: The Western Depiction of YPJ Combatants in Rojava. Glocalism: Journal of Culture, Politics and Innovation, 1. https://doi.org/10.12893/gjcpi.2019.1.7

Dehghanpisheh, B., & Georgy, M. (2016, November 4). Kurdish women fighters battle Islamic State with machineguns and songs. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-mosul-womenfighters-idUSKBN12Y2DC

Harding, S. (1991). Whose Science? Whose Knowledge?: Thinking from Women’s Lives. Cornell University Press.

Hartsock, N. C. M. (1983). The Feminist Standpoint: Developing the Ground for a Specifically Feminist Historical Materialism. In S. Harding & M. B. Hintikka (Eds.), Discovering Reality (Vol. 161, pp. 283–310). Kluwer Academic Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-306-48017-4_15

Hughes, C. (2019, June 20). Battle-hardened female troops fighting ISIS after vowing to eradicate caliphate. Mirror. https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/world-news/battle-hardened-female-soldiers-battling-16546076

Macharia, S., O’Connor, D., & Ndangam, L. (2010). Who Makes the news? (2010) [Global Media Monitoring Project].

Mahmood, M. (2015, January 30). ‘We are so proud’ – the women who died defending Kobani against Isis. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jan/30/kurdish-women-died-kobani-isis-syria

Perry, T. (2017, March 20). Exclusive: Syrian Kurdish YPG aims to expand force to over 100,000. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria-ypg-exclusive-idUSKBN16R1QS

Rollero, C. (2013). Men and women facing objectification: The effects of media models on well-being, self-esteem and ambivalent sexism. Revista de Psicología Social, 28(3), 373–382. https://doi.org/10.1174/021347413807719166

Shahvisi, A. (2018). Beyond Orientalism: Exploring the Distinctive Feminism of Democratic Confederalism in Rojava. Geopolitics, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2018.1554564

Sharda, A. (2014). Media and Gender Stereotyping: The need for Media Literacy. International Research Journal of Social Sciences, 3(8).

Smith, D. E. (1987). The everyday world as problematic: A feminist sociology.

Solomon, E. (2014, December 12). Women of 2014: The women of the YPJ, the Syrian Kurdish Women’s Protection Units. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/e0d911be-7fa6-11e4-adff-00144feabdc0

Subramanian, L. (2020). EXCLUSIVE: Kurdish woman fighters are finishing ISIS, smashing patriarchy. The Week. https://www.theweek.in/news/world/2020/01/10/exclusive-kurdish-woman-fighters-are-finishing-isis-smashing-patriarchy.html

Tank, P. (2017). Kurdish Women in Rojava: From Resistance to Reconstruction. Die Welt Des Islams, 57(3–4), 404–428. https://doi.org/10.1163/15700607-05734p07

Tartaglia, S., & Rollero, C. (2015). Gender Stereotyping in Newspaper Advertisements: A Cross-Cultural Study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 46(8), 1103–1109. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022115597068

Tavakolian, N. (2016, October 17). On the frontlines with the Kurdish female fighters beating back ISIS. Huck Magazine. https://www.huckmag.com/perspectives/reportage-2/kurdish-female-fighters/

About the author

Hoang Thi Kim Quy is a Master's student in the School of Law and Government at Dublin City University. She got an Irish Aid scholarship for the program at DCU in 2019. Her research interests include feminism and Kurdish guerrillas, and emerging alliances in the Middle East. She also had an MA in journalism (2016, AJC in Vietnam) and a BSc in Journalism (2013, AJC in Vietnam). Kim is a reporter in the field of international affairs for a state-owned online newspaper in Vietnam.

Comments

Post a Comment