Why has there been no Palestinian Arab Spring?

By Stephanie Dornschneider

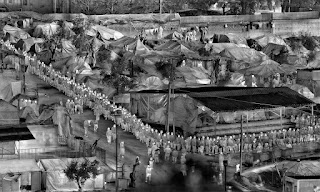

The armored dove. Banksy graffiti on the separation wall. (2017, Dornschneider)

Ten years ago, millions of Arab protestors suddenly brought down dictators who had been in power for decades. Within months, Tunisia’s Ben Ali, Egypt’s Mubarak, Yemen’sSaleh, and Libya’s Gaddafi were forced to leave. Like the protestors in these countries, Palestinians were suffering from severe grievances, due to political oppression and economic hardship. Yet, Palestine was one of the quietest settings during the Arab uprisings. What differentiates Palestinian non-protestors from Arab Spring participants?

My research on the reasoning processes underlying decisions to protest suggests that negative, risk-adverse thinking kept Palestinians from mobilizing. By contrast, participants in the Arab Spring embraced much more positive, risk-accepting thinking. Psychology research finds that emotions and affect are key to risk-related behavior, such as participation in the Arab uprisings. Rather than being mobilized through high levels of grievances, individuals may refrain from resisting their rulers based on insufficient positive thinking.

Protest is emotional

To explain the Arab uprising, much research focuses on structural factors, such as protest networks, autocratic institutions and their security apparatuses, or economic conditions. In the Palestinian context, the Israeli occupation and the costs of the 2000 intifada have been highlighted.

New research shows that emotions and affect are equally important, as found by the wider literature on psychology. Typically, the protest literature emphasizes the role of negative emotions of fear and anger. Fear is considered to deter protest behavior, whereas anger is considered to mobilize people for protest. However, my research finds that Palestinian non-protestors could not be differentiated from Arab Spring participants through anger or fear levels. Rather positivity and negativity were the key difference.

Anger, fear, negativity and positivity among Arab Spring protestors and Palestinian non-protestors (Dornschneider, work in progress)

To collect information about the reasoning processes of Palestinians, I organized ethnographic interviews in the West Bank and East Jerusalem. Ethnographic interviews apply nonintrusive questions that allow individuals to describe their behavior in their own words. I conducted interviews in the summer of 2017 with 32 individuals. The interviewees were not protesting at the time of the interview, and most of them never did. To find related information about participants in the Arab Spring, I examined 472individual responses to the call for the 25 January protests on the Egyptian Facebook group Kulana Khaled Said.

To analyze the data, I applied sentiment analysis, a quantitative method designed to abstract emotions and affect from text. The analysis was based on a lexicon that contained affect-laden words with positive, negative, and neutral values, as well as words indicating emotions of anger and fear. Examples of affect-laden words indicating positivity are “highest” or “charmed,” whereas “decay” or “damage” indicate negativity. Words indicating anger include “rage,” “outrage,” and “revulsion.” Fear was identified from words such as “anxious”, “abhor” or “abduction”. From the values associated with these words, the analysis calculated sentiment scores for the interviews and Facebook entries.

Protest is positive

The analysis finds that Arab Spring protestors are characterized by high scores for positivity and low scores for negativity (see Figure above). Palestinian non-protestors have higher scores for negativity than the Arab Spring participants, and similar scores for positivity and negativity. This suggests that positivity is an important motivator for protest, as suggested by recent psychology research showing that positive emotions of hope, solidarity, courage, and pride were crucial to mobilization during the Arab Spring.

The analysis also suggests that positivity is more important to differentiate Arab Spring protestors from Palestinian non-protestors than emotions of anger or fear. Contrary to expectations from the literature, Arab Spring participants do not display higher levels of anger than Palestinian non-protestors. Moreover, both groups show similar levels of fear.

In spite of comparably low levels of positivity among Palestinians, interviewees had not given up hope. In the words of a shopkeeper: “All of this pressure that they [Israeli authorities] are making has the goal of driving us out [of Palestine]. And in spite of all of this pressure that they are producing, the resistance becomes visible by us staying.”

--

Stephanie Dornschneider is the author of “Hot Contention, Cool Abstention. Positive Emotions and Protest Behaviour During the Arab Spring” (Oxford University Press) and “High‐stakes decision‐making within complex social environments: A computational model of belief systems in the Arab Spring” (Cognitive Science). This blog entry includes part of her ongoing research on resistance in Palestine.