Ethnic Cleansing in Jerusalem's Sheikh Jarrah

By Dr. Claudia Saba

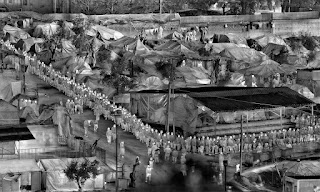

Damascus Gate, 'Bab Al-Amud', north-west entrance to the walled city of Jerusalem. Photo by: Claudia Saba, 2014

The recurrent episodes of carnage in the Israel-Palestine arena must be understood properly and acted upon accordingly if an end to them is desired. The death and destruction taking place as of May 2021 were sparked by the intended eviction of Palestinians in Sheikh Jarrah, East Jerusalem, from homes they have inhabited for generations. The families have been terrorized with the threat of eviction for years and on 10 May the Israel High Court was due to rule on the case, a ruling that has now been postponed in light of the popular uprising.

An analysis of the case through the lens of protracted social conflict theory is helpful to understand the complexity of the situation, particularly for new students of the conflict, though it is by no means the only lens through which to see it. For example, the Israeli polity has been theorized as a racist settler colonial state, a fair depiction when considering its treatment of Arab Jews, non-Jewish immigrants and asylum seekers as inferior races.

While the colonialism paradigm is compelling, here I offer an alternative theoretical framework through which to understand Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians, with the aim of dissecting the problem in a way that builds towards the establishment of a democratic state.

Political theorist, Edward Azar, was the first to theorize a Protracted Social Conflict (PSC) as a prolonged, violent struggle for basic needs and political access. Azar emphasized that PSCs occur more often within a state than between states. (For all intents and purposes, Israel-Palestine is a territory with one de facto government exercising draconian power over one of the two identity groups under its control.) PSCs are characterized by periods of low-level hostility interspersed with violent flare-ups. Such conflicts do not display clear start and end points. Although their intensity fluctuates, PSCs persist over long periods of time. What makes a PSC especially difficult to resolve is the interplay between four dimensions of hostility: the ‘communal content’, ‘human needs’, ‘governance’ and ‘international linkages’ dimensions.

Briefly, the ‘communal content’ dimension points to the presence of competing identity groups within the polity, whether they self-define according to ethnicity, religion or culture. Identity groups are engaged in a zero-sum struggle for resources. Azar notes, however, that it is the relationship between the identity groups and the state that is the core of the problem. The ‘human needs’ dimension refers to security, subsistence and political access. In a PSC these needs are mediated through the state, which acts on behalf of one group at the expense of the other. The dominant group essentially uses the state to maximize its interests. Azar notes that these arrangements are often legacies of colonial ‘divide and rule’ policies. In such systems the state is dominated by a single group or coalition and is at best unresponsive to the human needs of the subjugated group. The ‘governance’ dimension relates to the nature of the polity along the democratic-authoritarian scale. Governance in a PSC is characterized by authoritarianism, thereby exacerbating societal fragmentation and deepening the morass. Finally, ‘international linkages’ hitch identity groups to regional and international players in the political, economic or military spheres. These linkages further complicate the resolution of the conflict by concealing hidden levers of power. PSCs cannot be resolved unless they are treated in their totality and when all four dimensions are addressed.

The Sheikh Jarrah case exemplifies the ‘communal content’ aspect in that two identity groups have made competing claims over the same resource; the ‘human needs’ of one party have been denied through threats to remove them from their homes; the ‘governance’ by the state that controls their fate is discriminatory in nature; and the ‘international linkages’ of said state have aided it through pointed inaction.

The housing units in Sheikh Jarrah, built in 1956, were intended for Palestinian refugees through an arrangement between the United Nations and Jordan, back when East Jerusalem was still under Jordanian rule. They were built for Palestinian families that had fled the 1948 war which displaced them from their previous homes. After having lived in the Sheikh Jarrah homes for three years, Jordan issued ownership deeds to the families on condition that they give up their refugee status. The families have lived there ever since.

The threatened evacuations of the families are the result of a legal case taken by a Jewish settler organization, Nahalat Shimon. It alleges the land on which the houses were built had been owned by Jews before 1948. Their logic is that since Jerusalem was seized by Israel in 1967, it follows that previous arrangements do not stand. If Israel heeds this claim, as it has done in previous court cases over homes in Jerusalem, a total of 58 Palestinians, including 17 children, would be made homeless, and the dispossession endured in 1948 would be repeated. It is important to note that Israeli law allows Jews to reclaim lands lost in the 1948 war, but prevents Palestinians from recovering land and property they lost in the same war. Such unequal treatment by the state is but one of many laws Israel uses to confer superior status to the Jewish identity group. Such Israeli laws were recently found by Human Rights Watch to constitute a system that perpetuates crimes of persecution and apartheid.

Moreover, there is another body of law, International Humanitarian Law (IHL), that takes precedence over the laws of a sovereign country when that country occupies foreign territories. Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention prevents the transfer of an occupying power’s own civilian population into the territory it occupies, meaning that all Israelis who have settled in the occupied territories, including in Sheikh Jarrah, should not be there at all.

The Geneva Conventions have been cited ad nauseum to no avail. In 2004 they formed the basis of the finding by the International Court of Justice that the separation wall built to encircle and effectively annex Jerusalem was illegal. In 2016 the UN Security Council in Resolution 2334 cited the Geneva Conventions to urge Israel to 'abide scrupulously by its legal obligations and responsibilities'. Moreover, international law does not permit a state to enact security, legal or land policies in occupied areas. Israel has legal jurisdiction only over West Jerusalem.

For what it's worth, Jordan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has handed over 14 official documents relating to the building of the housing units, including a copy of the agreement signed with UNRWA in 1954. Thus far, lower Israeli courts had rejected such documentation. According to British Consul General in Jerusalem, Phillip Hall, specifically in the case of Sheikh Jarrah, Israel is in breach of international law.

Palestinians claim that the threatened evictions amount to forcible evacuation and ethnic cleansing, happening in real time and in full view of the International Community. Here is where Israel's powerful international linkages compound the problem. The International Community has not stopped previous evictions, though it had the power to apply pressure on Israel to prevent them. In the Skeikh Jarrah case, the EU expressed concern about the illegal nature of the planned evictions, but took no substantive action to stop them. Meanwhile, the US Department of State has said it is 'deeply concerned about the potential eviction of Palestinian families in Sheikh Jarrah' but focused the majority of its statement on the need to 'deescalate the situation' with no reference to the ethnic cleansing. This is unsurprising given US attempts to thwart an investigation by the International Criminal Court into crimes committed in the occupied territories, including the war crime of transferring Israeli civilians into the West Bank. Palestinian linkages with powerful external actors pale in comparison.

Over the past year and in light of the pandemic and its economic consequences, many European countries halted home evictions to safeguard their citizens, and many European states have long standing laws to protect those threatened by eviction due to bank foreclosures. That is what democracies do. No democracy worthy of the name ethnically cleanses in broad daylight.

-----

Dr. Claudia Saba lectures in International Relations at Ramon Llull University, Spain.

Comments

Post a Comment